Loving, stubborn, irreverent. To the aunty gone, but fondly remembered.

If there was one word to describe my aunty, it was irreverent.

On the few occasions when Mehrey Sanam babysat for my parents, she would pull up at the lights, fix you with an intent look, and extend a hand across the transmission.

“Pull my finger,” went the command.

“No, aunty,” you would protest.

“Pull my finger,” she insisted.

Mehrey’s ability to fart on cue, and to belch with complete disregard for propriety, made her—at least to my child self—something of a wildcard.

It was an impression doubtless shared by others, and one Mehrey Sanam was happy to play up to.

“Look at all these geriatrics,” she complaint during a family cruise trip, as if her 60-year-old self couldn’t have been more different to these silver-haired strangers enjoying their golden years.

“Mehrey T-sanam-i, they call me,” she cackled another time, referring to her fellow colleagues at the hospital where she worked.

It was, Mehrey went on to explain, not a reference to her destructiveness, but her reputation as a human dynamo.

A long-time operating theater nurse, Mehrey moved with the vigor of a woman half her age, sporting a devil-may-care smirk and a kind of gallows humor infused with mischief.

My aunty’s personal charms didn’t stop there. Mehrey regularly treated her colleagues to traditional Iranian hospitality with an assortment of homecooked meals.

While my aunty had a reputation for being generous to others, she was also never one to shy from the occasional self-indulgence either.

“$30,000?!” I cried, after learning the price of her new veneers.

“When I die they can take everything from me, but they won’t be able to take my teeth,” went Mehrey’s reply. She punctuated the joke with laughter, her lips curling back to expose the new pearly whites.

This kind of wry playfulness infused other aspects of aunty’s life. She named her first black-and-white cat Sylvester after the Looney Tunes character. When ever I asked where her pussycat was, she would break out in spontaneous song.

“What’s up pussycat? Whoa, whoa, whoa.” A line from a Tom Jones song, it turned out.

Sanam as it turned out was not Mehrey’s real last name, but a term of endearment used by one of her first boyfriends. A reference, my mother later told me, to one of Mehrey’s favorite Bollywood stars.

And while Mehrey herself had no interest being under the spotlight, she nevertheless had something of a movie star’s aura.

Perhaps it was Mehrey’s vanity; the habitualness with which she would open her compact and touch up the mandatory coating of eyeliner, mascara, and bright red lipstick.

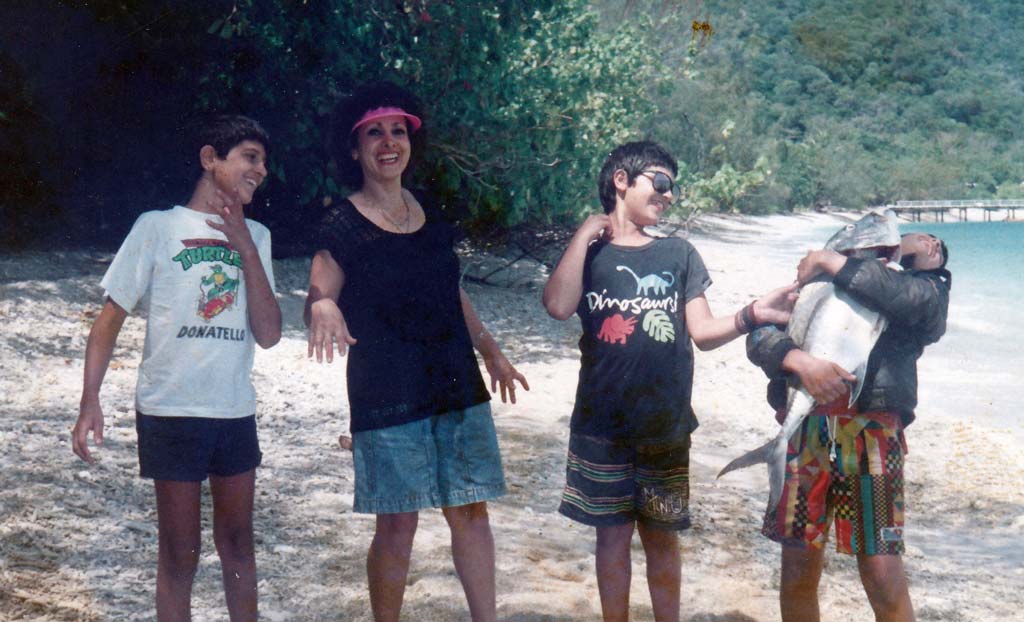

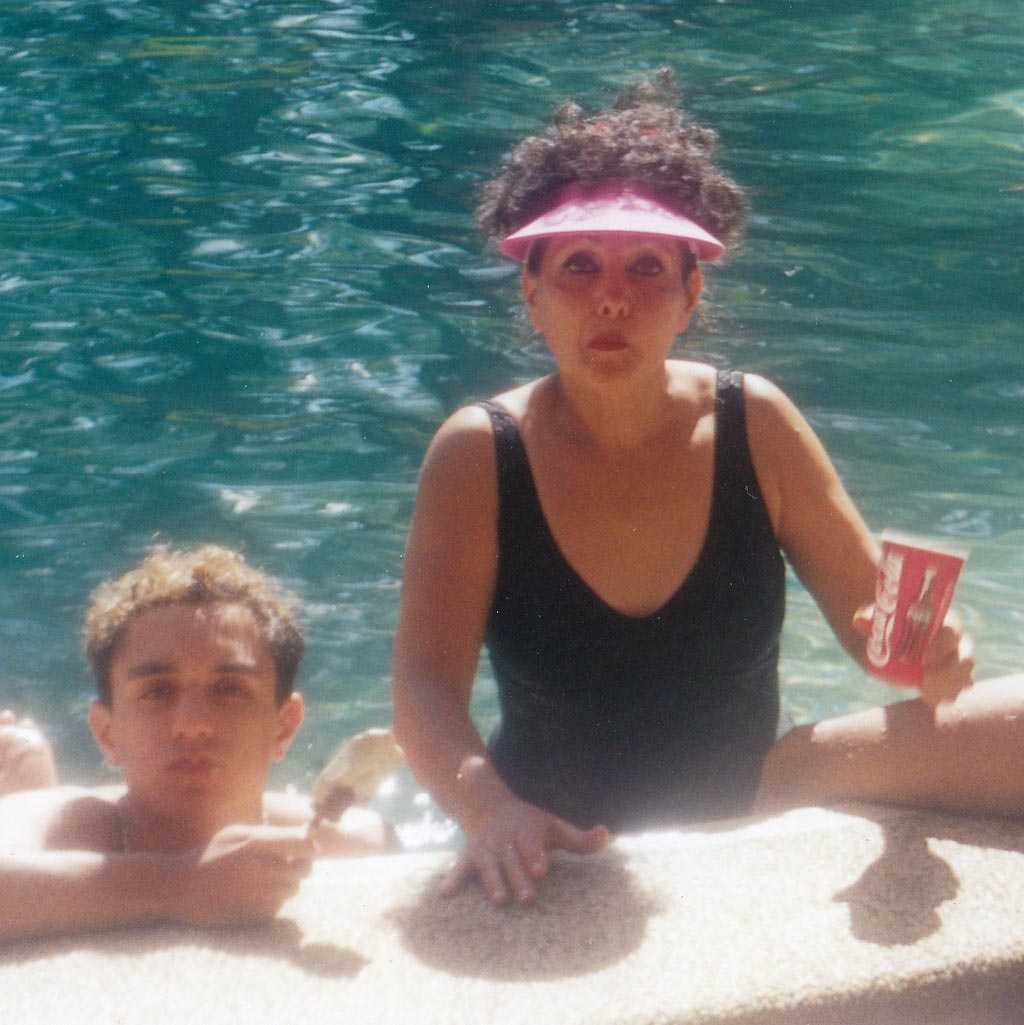

It was an appearance my aunty refused to shed, even during trips to a local river. Her hair suspended above a visor cap, Mehrey would enter the shallows, careful breaststroke keeping her face suspended a few inches above the waterline.

My siblings and I took delight in undermining our diminutive relative, splashing her with water or trying to dunk her when her back was turned.

Mehrey’s carefully made-up look did not change over the years. It cast her in my imagination as some bygone ‘50s star, fame forgotten, a personage whose name I could never remember. Lucille Ball, maybe.

Once, when my teenage sister and I snickered over Mehrey’s decision to not wear a bra (“Baggy soobs!” we said in our not-so-secret reverse language), Mehrey’s mouth tightened into a line.

“I do NOT have saggy boobs,” she retorted. “The women at work tell me I have the body of a TWENTY-YEAR-OLD!”

Mehrey’s aura may have also had its roots in her unapologetic stubbornness. It was a quirk that evoked admiration, but also generated a cool distance that not even her wit or laughter could completely bridge.

Still, as a child, I knew Mehrey was a dependable gifter, certain always to bring my siblings and me each a Kinder Surprise upon her visit. It conferred upon Mehrey the status of an ally, a patron saint of toys, treats, and cash; an opponent of parental authority.

Who else after all brought the sampler box of chocolates, oozing strawberry and peppermint cream? Who refuted our parent’s stern disciplinarianism and allowed us to play video games all day long?

Who did such unorthodox things as asking us to crack her spine by walking on her back? Who dared to break the anti-gambling rule of our religion by buying $2 scratch tickets?

Mehrey was a rebel, existing as a raised middle finger to anyone who might try to tell her what to do. Goodnatured defiance sat poised behind her heavily lashed stare; a stare almost feline in its assessment.

Not even nature was immune. When stung by a horsefly, Mehrey would stun it with a deft slap, catch the bug, and rip off first one wing, then the other.

“That’ll teach it,” she said, with a hint of mean satisfaction.

Another time, Mehrey rolled down our car window and performed a racist imitation of an Asian driver who had cut my father off.

The course of Mehrey’s life served as further proof of this role. She had left everything she had loved and known to emigrate to Australia in pursuit of a better life.

Mehrey had married and eventually separated from her husband, taking it upon herself to raise their three boys on her own, often working two jobs to keep the family afloat.

My aunty’s decision to take the name Sanam was not so much a f*** you to her husband or the institution of marriage, but a capstone upon the walls she’d built around her life. Stone by stone, Mehrey had assembled the image of herself as an independent, self-made woman.

It was an image not born of bitterness, but resilience. And it was—in many respects—well-earned.

Over the course of Mehrey’s life, she owned several businesses, including a fabric store and ice cream counter. When these businesses failed, she turned her hand instead to leasing a lychee plantation and recruiting her three sons to pick fruit.

Mehrey proved a woman of many secret talents. She oversaw the design of her new home and planted gardens teeming with spiny custard apples, swollen melons, and speckled papaya.

My aunty host lavish gatherings at her home for members of the local Baha’i community. During devotionals, Mehrey would chant prayers in a voice that was melodic, heavy with the suggestion of some tragic loss.

My aunty sang like a bereft lover, yet the woman we knew surely had never loved any man with such intensity as this.

Mehrey’s performances would inevitably draw praise and requests. And this seemed to embarrass her in the same inexplicable way my mother’s birth name “Tahirih” (meaning “the pure”) did.

Suffice to say, Mehrey’s secret talents served a function. It was a kind of overcompensation, sometimes for challenging life circumstances, other times for the things Mehrey lacked and could not offer.

My aunty was for example never much one for physical affection, and yet she didn’t hesitate to force vitamin supplements upon all of her family members. This was, I knew at the time, her way of demonstrating that she cared.

Mehrey’s entrepreneurial nature eventually led her to invest in a new side hustle: backyard botox. My mother disdained this new interest, warning her sister that practicing without a license would land her in hot water.

Mehrey of course waved away these doubts the same way she had always done. What use did they serve anyhow? Doubt had never done much to ensure my aunty’s and her family’s survival.

And Mehrey was a practicing surgical nurse with decades of experience working with complex cases, from car accidents to open-heart surgery. What more training did she really need?

To me, Mehrey’s new hustle was about as outrageous as the person herself. It was a logical conclusion for someone who so prided herself in appearance and bucking trends.

Unlike the $2 scratch tickets Mehrey so adored, however, the botox business did not pay off. When one patient had an adverse reaction to an injection, Mehrey was reported to medical authorities.

My aunty soon found herself embroiled in a lawsuit, costing her both her nurse’s license and—at least in her own mind—her dignity.

The shame of these circumstances took the fight out of my aunty. This once unflappable powerhouse became instead a frail, broken woman, bowed beneath the weight of shame.

Mehrey stopped eating and began doctor shopping for opioid painkillers. Aware of her declining health, I reached out to my aunty, begging her to come and stay with me.

Offering to buy her an airline ticket, I reminded Mehrey of everything she had done for me, of how precious her life was to all of us

“Thank you, Ehsan,” she said. “You made me feel much better. You’re my favorite nephew.”

The relief in Mehrey’s voice I knew was temporary. Her fierce determination—a determination that had carried her this far, through many a difficulty—was now leading her towards a terrible destination.

Two weeks later, Mehrey was found comatose in her bed. Her brain functions were nil, the result of oxygen deprivation, linked to her growing reliance on opioids.

My family attended Mehrey’s hospital bedside, peering tearfully down at the shell of the woman we had once known.

The idea of touching her terrified me. I struggled to communicate my love to this bag of insensate flesh and bones that had betrayed Mehrey’s spirit by refusing to simply die, as I suspected she had wanted it to.

The decision was made to withdraw life support, and Mehrey passed not long after. A dread hush fell over our family, a hush that would last for many years to come.

It was as if speaking my aunty’s name alone could conjure the unspeakable and unspoken; a story that had ended abruptly, without explanation, and with none of the ceremony deserving of a person and life as rich and triumphant as hers had been.

In the years since I would walk back down the halls of memory to the days of monsoonal rainstorms. I would remember how Mehrey’s older sons—our cousins—would push us on boogie boards across the flooded field behind her home.

I’d think of aunty’s requests to turn off the fan on hot days, on the account of her being, in my father’s words, a “coldblooded lizard”. Of how she fought off the python that smothered her beloved cat just with a broom.

Of how my sister and I walked among the rafters of an incomplete roof of her home and left a crack in the ceiling, a crack that rankled Mehrey to no end, but for which she nevertheless forgave us.

I laugh when I recall Mehrey’s chagrin over the fact she’d allowed relatives in Iran to persuade her to get eyebrow tattoos, only for them to turn green within a matter of months.

And I shake my head at a tale that would later emerge of how a putupon mother had tied the leg of her eldest son to a tree and left him there, as punishment for some childhood misdeed.

Mehrey’s life served as a fierce testament to the strength of her personality, as a kind of rationale for the way she had chosen to live. But with my aunty now gone, who was there left to speak for her?

Who, I wonder, would keep a candle lit for this beacon of strength—a beacon once so vital, so seemingly unquenchable?

My aunty was a character of many conflicting qualities. A lover of black humor. Purehearted, occasionally prideful, and inflexible in a way that was, more often than not, strangely endearing.

Mehrey was an individualist who insisted on keeping her own counsel…and keeping at arms-length. A fighter who insisted on always having the last word.

I take strange comfort in the fact that, in the end, my aunty did. For beneath her headstone lies buried a pair of perfectly intact veneers, set in an eternal grin.

Essy Knopf is a therapist who likes to explore what it means to be neurodivergent and queer. Subscribe to get all new posts sent directly to your inbox.