Confessions of a Control Freak – Part 1: An Obsessive Compulsion

Cocktail: The Joykiller.

Description: The perfect cocktail for the aspiring wet blanket.

Ingredients: Four ounces of perfectionism, a dollop of workaholism, a splash of stubbornness. Method: Mix, shake well, strain into a glass of rigid thinking. Serve with a twist of stinginess.

Confessions of a Control Freak is a memoir blog series exploring the impact of Obsessive Compulsive Personality Disorder, its origins, and the rocky path to recovery. Names and identifying details have been changed to protect the privacy of all featured individuals. Subscribe to receive all future posts. More about OCPD here.

I

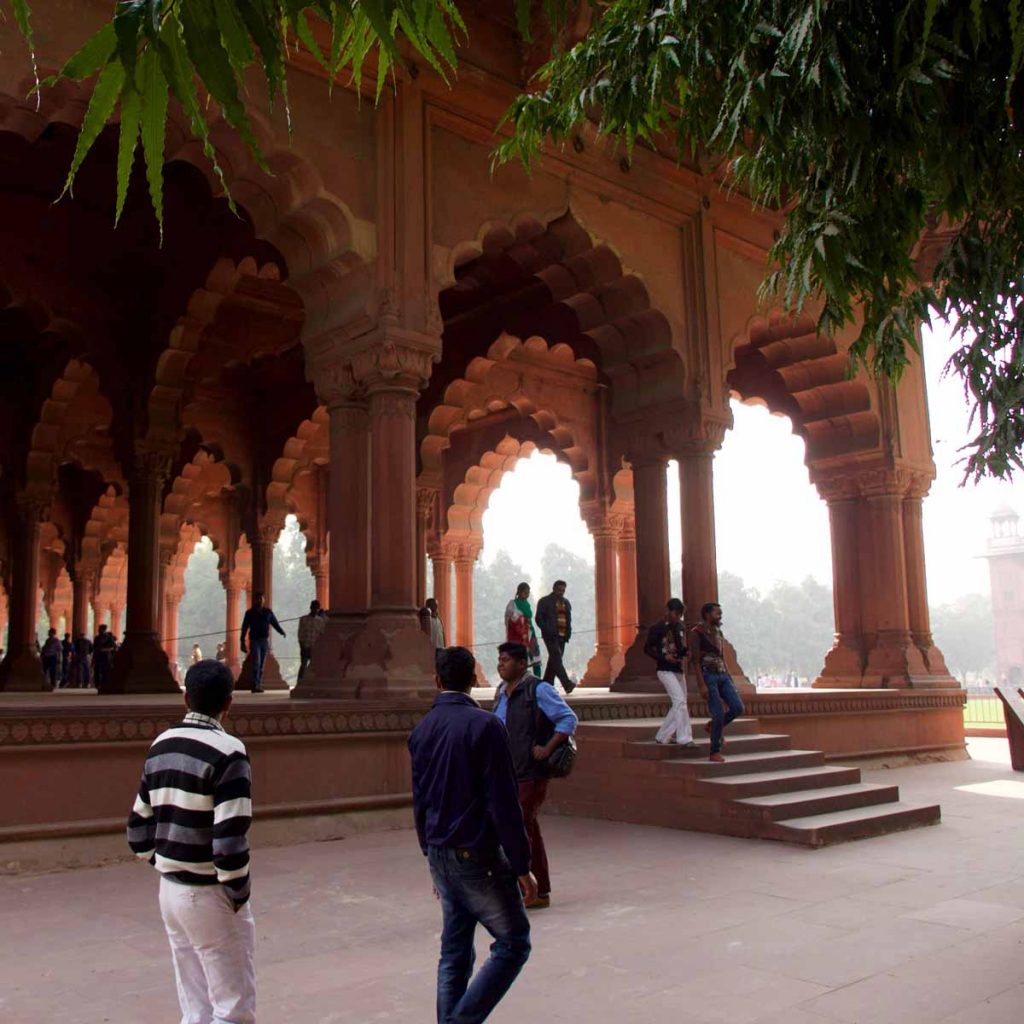

Exploring India for most people may sound like a great way to spend a vacation, but for someone with undiagnosed Obsessive Compulsive Personality Disorder (OCPD), it was an unmitigated disaster.

Days before my trip, I completed a web series and the first draft of an alternate history fantasy novel—one of several creative projects on a never-ending, self-perpetuating carousel of work.

Having accrued more than a month’s worth of leave, I decided that the best way to spend my time “off”, naturally, would be to start yet another project.

No, I was not going to be going on an adventure and collecting photos for a post-trip slideshow with family and friends.

Instead, I was going to conduct research for a novel—a sequel to another book I technically hadn’t even finished yet. Talk about getting ahead of myself!

I booked a ten-day guided tour around the arid northern Indian state of Rajasthan, once a patchwork of princely states under the British Raj.

This I figured was the very least amount of time I would need to document every inch of my surroundings. I couldn’t afford to miss a single thing.

Printing a copy of my novel draft, I packed my camera and boarded my flight. First stop: Mumbai, where I spent a few days visiting a friend, before striking out on my own to New Delhi.

The next ten days passed in a frantic blur. When I wasn’t snapping photos at some site of historical significance, I was ensconced in my hotel room bed, eating from room service trays as I scrawled notes on my already-dog-eared manuscript.

Room service would knock and I would bark a reply. My sheets and towels didn’t need changing, thank you very much. I could manage just fine with the ones I had.

If I had hoped to soak up the ambiance of my surroundings, I found myself too preoccupied to do even that.

Instead, I found myself staring down, first in confusion, then horror at the metal nozzle projecting on from the toilet seat, not quite ready for the culture shock presaged by a bidet.

When I was outdoors, I distracted myself with a packed schedule. This meant that I was, more or less, constantly moving at a sprint, checking off sightseeing to-do lists in advance of my departure for Rajasthan.

Relaxing, I told myself, would be a waste of my hard-earned leave time, and a plane ticket to boot. Ever the master of delaying gratification, I told myself I could take a proper vacation later, some other time, but only after I had truly earned it.

II

This unwillingness to relax took its toll, however, and by the time the touring car finally arrived to whisk me away to Rajasthan, I was practically manic.

I may have already conducted a ton of research, and yet I still hadn’t completed the second draft of my novel.

Then there was the irksome fact I’d had to sacrifice a crucial train trip to several UNESCO World Heritage sites due to last-minute itinerary changes.

Having planned my visit with the goal of literally seeing everything possible, the completionist in me ached with the idea that I might miss a single thing.

And given my life was already bursting with other commitments, I couldn’t reasonably expect I’d be making a return trip anytime soon.

For the remainder of the ride to Rajasthan, I sat in the back of the car, earphones in, head bowed, reviewing page after page of my manuscript.

If I’d hoped to take satisfaction in my progress so far, I instead found the novel to be sorely wanting. The dialogue was clumsy, and the characterizations paper-thin.

Desert vistas crawled past my car window, and crumbling stonework ruins whizzed by, but I didn’t see them.

My driver slowed the car, pointing out to me grazing antelope. I looked up only long enough to feign wonderment, before resuming striking out text and scribbling corrections.

At the end of each day, I would lock myself in my hotel room and refuse to come out. There was still too much work to be done.

When people dragged their chairs in the restaurant one floor above, generating what sounded like thunder in my room directly below, I complained about the noise to the hotel receptionist.

Didn’t these people realize I was engaged in serious work, churning the next cross-genre literary masterpiece?

How lucky they must be, these carefree vacationers. They didn’t carry with them multiple internal timepieces that were forever ticking over. They didn’t have to fear ceaseless deadlines.

When one hostel I was staying in notified me that hot water was only available one hour of the day, I barked at the receptionist.

Didn’t he understand I ran on my own schedule? That I had places to be and things to do?

III

My anger was proportional only to my dissatisfaction with myself. Forever hovering over me was the dreaded realization that there would need to be many more rewrites before my novel would be fit to show to the world.

And even then, when I finally did, time and distance would reveal to me a dozen blindspots that had gone unseen and undermined all my carefully planned and meticulously researched story sequences.

This was a position I had more or less already arrived at the minute I’d wrapped work on the first draft.

If there wasn’t a problem, I would be sure to find one. My reasoning? It was better to preempt criticism and get the jump on disappointment than suffer a sucker punch from a stranger.

With each leg of the journey, my tour driver grew increasingly agitated, hunching over the wheel like someone with chronic road rage, intent on mowing down whoever might cross his path.

He stopped offering me free bottles of water and stopped calling my name. I was no longer “Mr. Ehsan”, but someone to be addressed strictly out of necessity—and only then in a clipped voice.

When, finally, I asked him what the matter was, he revealed he had been expecting to receive a daily tip from me.

In the years of chaperoning foreign vacationers during the height of the tourist season, my driver had apparently never met someone who clung as stingily to my purse strings as I had.

In my defense, however, I had already paid a princely sum to the tour company.

And then there was the fact that in my home country—Australia—we simply didn’t tip. Never mind my driver was expecting only a nominal amount. Not tipping him was, I told myself, a matter of principle.

Besides, I’d practically spent all the money I had getting here. And let’s remember, this wasn’t a true vacation, but a research trip.

I wasn’t some privileged Westerner with deep pockets, but a reluctant martyr for my own ambitions.

This approach did not go down very well with one of my tour guides. When I failed to tip him at the end of our two-hour-long walk, he stood over me, glowering. I pretended not to notice.

As far as I was concerned, he was the one who had breached social norms by expecting payment on top of the fee he’d already received from our tour company.

IV

The rest of the trip slipped by like an afternoon dream: majestic hill forts of gold sandstone, soaring pink city walls, a shimmering sprawl of blue buildings at the edge of the Thar desert.

Towards the end, I climbed a hill to a viewpoint frequented by tourists. Local kids had gathered to fly kites or beg politely for pencils.

One of them was singing, accompanied by a wizened man on the harmonium.

As I watched the sun dip toward the horizon, I was struck by the realization that for all the beauty that surrounded me, I was not moved. I felt in some ways cut off, my feelings trapped behind a rigid, impenetrable shell.

Since my late teens, all I’d was a steely determination to survive in the face of whatever hardships might be thrown in my path.

The skies turned from gold to amber to umber. The young singer crooned a final, wistful tune. A crack appear in the shell, and suddenly I was crying.

I felt like a jack-o-lantern that had its insides scraped out. Empty, and exhausted.

Then came the profound sense of loneliness—a stalwart companion from earlier days.

Rigidity as a survival mechanism

This same loneliness I credited for launching my never-ending crusade of workaholic perfectionism.

Since my late teen years, I felt perpetually harried by a need to be productive. I’d create lists of things I wanted to achieve and, one by one, ticked them off with machine-like efficiency.

My default was “bustling”. When I wasn’t running to catch buses or bolting from commitment to commitment, I was writing a new story, shooting a new film, and undertaking a new degree.

My home was not a sanctuary—it was a workplace. I spent most of my time in front of my computer, taking the occasional break to tidy, clean, cook, and work out. When I wasn’t running on a physical treadmill, I was always running on a figurative one.

Nothing I did was ever good enough; I could always do better. Everything was a problem to be fixed. There was forever room for improvement.

This philosophy extended to not just my life, but that of others as well. If all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail, and I hammered away to the detriment of my relationships.

In my mind, this behavior had the perfect rationale. I was someone with big dreams, the job I was doing wasn’t my true passion, and I lacked any sense of financial security.

The only way I was going to rise above these obstacles was by applying myself.

These standards I had set for myself, however exacting they might seem to others, were in my estimation fair.

If I could learn to follow them with religious zeal—so why couldn’t they?

As righteous as I felt on this path, what I failed to acknowledge was that this work I endlessly generated for myself was really just a kind of coping mechanism.

For too long, I had been troubled by the sense that something fundamental was wrong in the world; something that threatened my sense of wholeness, worthiness, and safety.

But so long as I stayed in the saddle of workaholism, I could avert the many impending crises I imagined loomed large over my life.

Grandiosity, or Obsessive Compulsive Personality Disorder?

My behavior, I would later learn, had all the hallmarks of Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder (OCPD).

OCPD, according to the DSM-5, involves a more “a pervasive pattern of preoccupation with orderliness, perfectionism, and mental and interpersonal control, at the expense of flexibility, openness, and efficiency”.

Key traits of OCPD include:

- Preoccupation with details, rules, lists, order, organization, or schedules

- Perfectionism that interferes with task completion

- Excessive devotion to work and productivity

- Being overly conscientious, scrupulous, and inflexible about matters of morality, ethics, or values

- Being unable to discard worn-out or worthless objects without sentimental value

- Reluctance to delegate tasks or to work with others unless they follow your precise way of doing things

- A miserly spending style

- Rigidity and stubbornness

A distinction should be made here between OCPD and the better-known Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder.

People with OCD experience uncontrollable, persistent thoughts (obsessions) and behaviors (compulsions), which they often have some degree of insight about.

People with OCPD on the other hand cling to their way of doing things and seem comfortable with their self-imposed systems of rules, believing nothing is inherently wrong with their style of thinking.

A positive diagnosis

My trip to India represented a crisis point in my life. The rigid habits, rules, and structure by which I’d lived my life had been challenged, and the control I was forever grasping was slipping from my grasp.

When presented with demands to change, rather than making the necessary concessions, I dug in. Unstoppable force, meet immovable object.

The misunderstanding and misery that had resulted could, in hindsight, have easily been averted.

I could, for example, have surrendered my constant need for productivity and been more mentally present, and actually enjoyed this once-in-a-lifetime experience.

I could have also smoothed ruffled feathers by tipping my driver and guides, rather than stingily withholding.

It would take some years—and many more immovable objects—however, before I would achieve true insight into my behavior.

And even then, surrendering my self-appointed moral high ground would prove no easy task.

Confessions of a Control Freak continues with Part 2: “An excess of perfection”.

Essy Knopf is a therapist who likes to explore what it means to be neurodivergent and queer. Subscribe to get all new posts sent directly to your inbox.