10 must-read books for gay men seeking growth, healing, and an escape from the struggle mindset

The coronavirus lockdowns gave us time aplenty to stew and fret. Some of us however took it that time to play “life catch up” or even to undertake personal growth and healing.

As a gay man, I know that it’s precisely when life begins to slow down that I find both the time and the mental bandwidth to seek out the personal insights necessary to said growth.

At the time, I proposed the following reading list to help jumpstart the journey for anyone walking a similar path.

While the worst of the pandemic is largely behind us, the lifelong quest for self-knowledge continues. The following 10 self-help books I consider mandatory reading for this quest. Here’s why.

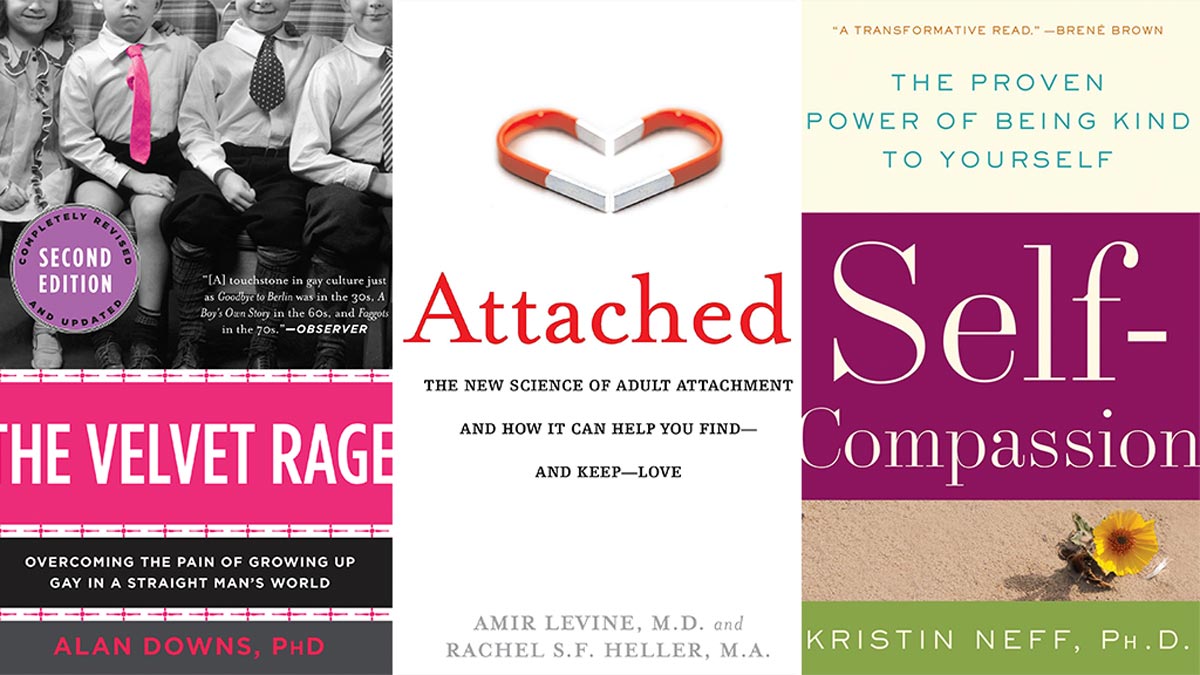

Understanding the gay struggle – the first step towards growth and healing

“Something about growing up gay forced us to learn how to hide ugly realities behind a finely crafted façade. Why is this so? We hid because we learned that hiding is a means to survival.”

– Alan Downs, The Velvet Rage

Even as an out and proud gay man, I felt like I was still living a life of subterfuge. Only now it wasn’t my sexuality that I was hiding but my vulnerability.

My dating experiences revealed I wasn’t the only one struggling with an entrenched sense of self-loathing and shame. More than a few of us had been left emotionally crippled by our experiences.

Not only were we incapable of building robust relationships—we were also prone to seeking relief through substance and process (behavior) addictions.

The Velvet Rage argues however that there is cause for hope. Author Alan Downs charts the journey gay men must take from self-loathing to self-acceptance before concluding with a raft of invaluable suggestions for how we can live happier and healthier lives.

Transforming your life through vulnerability

“Vulnerability is not weakness, and the uncertainty, risk, and emotional exposure we face every day are not optional. Our only choice is a question of engagement. Our willingness to own and engage with our vulnerability determines the depth of our courage and the clarity of our purpose.”

– Brené Brown, Daring Greatly

When I came out as gay, I was searching for connection and a sense of belonging. I was, in a way, looking for a replacement family for the one from which I had become alienated.

Initially, I looked for it at gay venues, like bars and clubs. I quickly learned that it was sex, not vulnerability, that many of the men I met were looking for.

These individuals might claim to have achieved self-acceptance, and yet their aversion to vulnerability was so total, the denial of shame so complete, that our relationships remained mired in superficiality.

Any invitation to be emotionally authentic was met with bewilderment, resistance, and even scorn. To those I encountered, being vulnerable was at best weak, at worst dangerous.

Daring Greatly author Brené Brown argues that this need not be our fate. “Shame,” she writes, “derives its power from being unspeakable. Shame keeps us small, resentful, and afraid”.

Her solution? Recognize it for what it is, understand its triggers, strive for critical awareness, and be willing to reach out to others and speak out about our shared experience of shame.

You can watch Brown’s TED talk on vulnerability here.

Recognizing the influence of trauma

“Traumatized people are terrified to feel deeply. They are afraid to experience their emotions, because emotions lead to loss of control… Being traumatized is not just an issue of being stuck in the past; it is just as much a problem of not being fully alive in the present.”

– Bessel van der Kolk, The Body Keeps the Score

I was 12 when my family began to fall apart. My older brother’s daily battles with my parents, his drug use, and random acts of violence, lying, and thievery reduced our household to a warzone.

My parents eventually buckled under the strain of it all, withdrawing emotionally and giving my brother free rein to bully me.

The experience left me stricken with an unrelenting sense of loneliness and worthlessness.

Trauma was a word I exclusively associated with veterans or victims of extreme abuse. But as I came to later learn, trauma can be entirely passive, like emotional neglect.

Trauma for gay children is an all too common experience. We face it when we are rejected, assaulted and even cast out for our sexuality.

Bessel van der Kolk’s comprehensive The Body Keeps the Score is a deep dive into the manifestations and mechanics of trauma.

Readers will come away from it with new insights not only into their own experiences with trauma but possible treatments as well.

Adopting optimistic thinking

“An optimistic explanatory style stops helplessness, whereas a pessimistic explanatory style spreads helplessness. Your way of explaining events to yourself determines how helpless you can become, or how energized, when you encounter the everyday setbacks as well as momentous defeats.”

– Martin Seligman, Learned Optimism

While my family was disintegrating, I was also being bullied at school due to a then-undiagnosed disability, Asperger syndrome.

My resulting depression and anxiety led to what Learned Optimism author Martin Seligman calls a “pessimistic explanatory style”.

In moments of difficulty, I would resort to self-blame, telling myself I was unlovable and entirely deserving of my misfortune. These explanations came at a great cost to my mental wellbeing.

Learned Optimism argues that we can correct this chain of thinking by identifying the adversity we’ve experienced, the existing beliefs they trigger, and their consequences. By disputing these beliefs, we can alter the impact they have on us.

You can discover your own explanatory style with the help of this quiz devised by Seligman.

Being kinder to yourself

“Self-compassion provides an island of calm, a refuge from the stormy seas of endless positive and negative self-judgment so that we can finally stop asking, ‘Am I as good as they are? Am I good enough?’”

– Kristin Neff, Self-Compassion

Previously I’ve discussed the burden of “grandiosity”, a defense used by gay men against feelings of inferiority or covert depression.

The one thing I’ve found key to my recovery as a workaholic perfectionist is the very thing I’ve denied myself: self-compassion.

When our attachment as children to our primary caregivers is disrupted (more on this below), we fail to develop critical self-soothing skills.

This may cause us to neglect our own needs during times of stress or suffering. We may even seek distraction in grandiose or self-destructive behaviors, like addiction.

Self-Compassion author Kristin Neff offers a third alternative: practicing self-soothing through mindfulness, being aware of our emotional states, and responding appropriately to them with words and acts of compassion.

Adopting a ‘growth’ mindset

“Believing that your qualities are carved in stone—the fixed mindset—creates an urgency to prove yourself over and over… Every situation is evaluated: Will I succeed or fail? Will I look smart or dumb? Will I be accepted or rejected? Will I feel like a winner or a loser?”

– Carol S. Dweck, Mindset

Those fixed in their thinking, like grandiose gay men, are stricken by a fear of failure and imperfection.

As such, they seek success in the place of growth, superiority rather than self-acceptance.

But, as in the words of Mindset author Carol S. Dweck: “If you’re somebody when you’re successful, what are you when you’re unsuccessful?” The fall from such heights can be devastating.

The opposite of a fixed mindset is the growth mindset, which calls for us to suspend constant judgment of ourselves and others. A growth mindset makes us more likely to seek out personal change and development.

The good news is we don’t have to be born with a growth mindset to enjoy the benefits. We learn to adopt one through practice.

Setting clear boundaries

“Setting boundaries inevitably involves taking responsibility for your choices. You are the one who makes them. You are the one who must live with their consequences.”

– Henry Cloud and John Townsend, Boundaries

Boundaries are crucial for all gay men because our right to choose how we live is one that often comes under the scrutiny and judgment of others, especially our own families.

As a gay man who enjoys a close relationship with my mother, I can safely say that it was one arrived at through continual negotiation, and a willingness to defend my personal boundaries.

My transition to independent adulthood was predictably rough. My mother, for reasons that were perfectly logical to her at the time, would insist on trying to control or judge aspects of my life even after I left home.

My decision to get a mini-mohawk, for example, would result in the silent treatment. Piercing my ears resulted in her nagging for me to “take them out”.

In moments of weakness, I would kowtow to her will, at the cost of mutual respect.

Renegotiating boundaries with our parents can be a particularly thorny process, yet it is critical to the longevity of your relationship as well as those that follow.

While the non-religious may struggle with Boundaries’ numerous Biblical references, Henry Cloud and John Townsend’s classic remains a vital guide to establishing better relations with our loved ones.

Understanding your relationship needs better

“People have very different capacities for intimacy. And when one person’s need for closeness is met with another person’s need for independence and distance, a lot of unhappiness ensues.”

– Amir Levine and Rachel Heller, Attached

Dating for me has historically been an uneven game of push-pull; a mismatch of varying needs and expectations.

It was only when a friend introduced to me the concept of attachment styles that the cause was at last brought into focus.

Our relationships with our primary caregivers from our childhood onward serve as a template for how secure we feel in the world. It also forms the basis for how we “attach” to others.

Attachment falls into three categories: secure, anxious, or avoidant. Anxious people seek closeness and affirmation, avoidants seek distance and independence.

Secures typically have no difficulty bonding with either type and thus serve as an ideal partner for anxious and avoidants.

While this all sounds rather formulaic, being able to recognize your own needs as well as that of your romantic partner is a guaranteed way to save both of you a lot of difficulty—and heartache—down the road.

Those interested in identifying their’s or other’s attachment styles can try this brief quiz by authors Amir Levine and Rachel Heller.

Learning to meditate

“Mindfulness is moment-to-moment non-judgmental awareness. It is cultivated by purposefully paying attention to things we ordinarily never give a moment’s thought to. It is a systematic approach to developing new kinds of agency, control, and wisdom in our lives, based on our inner capacity for paying attention and on the awareness, insight, and compassion that naturally arise from paying attention in specific ways.” – Jon Kabat-Zinn, Full Catastrophe Living

In Full Catastrophe Living, author Jon Kabat-Zinn explains that while stress may be an unavoidable feature of life, how to deal with it or not deal with it is ultimately our choice.

For example, the trauma I experienced growing up was hardcoded into the behavioral circuitry of my brain. I found that later conflicts would invariably trigger them.

The resulting fight-or-flight response was often destructive to my relationships.

It was possible however to reprogram my brain to judge and react to every stimulus. This is the essence of self-awareness.

By practicing exercises like diaphragmatic breathing and meditation, we can learn to be present with our experience. Through mindfulness, we can learn to be aware of our feelings, rather than controlled by them.

Improving emotional intelligence

“People with well-developed emotional skills are also more likely to be content and effective in their lives, mastering the habits of mind that foster their own productivity; people who cannot marshal some control over their emotional life fight inner battles that sabotage their ability for focused work and clear thought.”

– Daniel Goleman, Emotional Intelligence

The skills described above – self-awareness (knowing one’s own emotions) and self-compassion (managing those emotions), as well as self-motivation, empathy, and relationship management – are all critical to what Daniel Goleman calls “emotional intelligence”.

Emotional intelligence is a meta-ability that governs how successful we are in all aspects of our lives, from relationships to our wellbeing, to personal effectiveness and productivity.

My discovery of Daniel Goleman’s seminal work served in this sense as a catalyst for confronting my own trauma and seeking a fresh perspective on my struggles.

I accomplished this with the help of therapy, reading self-help and psychology books, opening up dialogues with others, and yes, undertaking meditation.

While some sections and theoretical discussions may not be relevant to all readers, Emotional Intelligence is an essential read for all gay men on the path of self-improvement.

Essy Knopf is a therapist who likes to explore what it means to be neurodivergent and queer. Subscribe to get all new posts sent directly to your inbox.