Be kind. Stop the oppressive cycle of internalized gay shame.

My lack of body coordination has always been a painful fact, evoking a gay shame that stems from my school years.

Raised in the stoic, sports-oriented culture of Australia, I often felt that my value as a male – at least in the eyes of my peers – was ultimately tied to my athletic prowess and sexuality.

It was not until my diagnosis with Asperger syndrome (autism) at age 26 that I found myself able to shrug off the feelings of masculine “inferiority” that had dogged me for so long.

Where previously I’d treated sports as a high-risk arena for failure, I now decided to turn this arena into a sandpit of experimentation.

After dabbling in cycling ended with me lodged in a stranger’s windshield, I turned to kickboxing instead.

While waiting for classes to begin, I’d watch the invite-only advanced members amble out of the ring, self-assured in a way I could never hope to be.

Coveting the brass ring corroded my enthusiasm. All it took was one badly aimed kick landing in a stranger’s family jewels for me to decide to pack it in.

Judgment and toxic masculinity

My next stop was an LGBTQ+ recreational dodgeball league. Despite being a lousy aim and an easy mark, I was determined to commit to at least one season of play.

My team members proved for the most part friendly. Longtime players seemed unsparing in their support of newcomers, doling out praise and tips.

But what had begun as something casual very quickly into an exercise in extreme competitiveness, as gay judgmentalism – normally grounded in the assessment of other’s physicality – now found focus in player’s on-court capabilities.

It was present in how some league members ignored friendly overtures, in the way cliques closed ranks upon approach.

I witnessed team captains actively scouting games and handpicking members, choosing some while excluding others. Never mind that this was a recreational league.

Worse still, players would yell at one another for failing to catch balls. While dodging one ball, I found myself on the receiving end of a rude shove from another team member.

Then there were the players who strutted about with an air of superiority, engaging in dizzying displays of skill and berating first-time players for not knowing the rules.

The behavior grew more ugly from there. Some players flagrantly defied the rules while the coaches weren’t watching, refusing to take their “outs” as if it were a matter of survival.

This inevitably led to verbal clashes, taunting, and the exchange of obscenities. Par for the course with any competitive sport – and yet an LGBTQ+ league was the last place I’d ever hoped to endure toxic masculinity.

Some people, it seemed, were replaying far older battles, where the stakes weren’t so much team ranking, as they were self-worth.

A secret legacy of gay shame

In any LGBTQ+ sports league, there’s always an argument to be made for the commonality of our struggles.

As many of us have endured exclusion and bullying over our sexuality in the past, this is probably the last thing any of us would want to inflict upon others. So why does it continue to happen?

Society historically has regarded gay men with contempt, constructing our sexuality as either a despicable choice, a weakness of character, or a moral flaw.

Our way of coping with this atmosphere of psychological, social, and even physical danger according to The Velvet Rage author Alan Downs is by adapting, chameleon-like, to our surroundings.

We conceal visible expressions of our gay identity, such as our interest in members of the same sex. And we suppress expressions of traditionally “feminine” traits, such as emotional vulnerability, while muting our authentic selves.

In short, we make ourselves more acceptable to others, at the expense of our own wholeness. And in so doing, we internalize others’ judgment.

Being told our “perversity” is a choice, and believing this not to be the case, we are faced with an internal dispute. We find ourselves harboring what feels like a terrible secret. Other’s contempt thus becomes our shame.

As young adults emerging from the repressive social environments of our childhood, we may leap headlong into expressions and declarations of self-acceptance; “wrapping ourselves in the gay flag”, as it were.

Such expressions and declarations however represent a destination that can only be reached after a certain internal journey requiring some degree of excavation, examination, and healing.

As Brené Brown explains in The Gifts of Imperfection, “Shame needs three things to grow out of control in our lives: secrecy, silence, and judgment. When something shaming happens and we keep it locked up, it festers and grows. It consumes us”.

Gay shame, when left unaddressed, may even find expression, contrarily, in the form of more contempt.

Calling out shame

The behavior I witnessed – the exclusion, the general disrespect towards others, and the desire to win at all costs – meant that old traumas were being exhumed.

It also meant that players who had once themselves been oppressed were now unwittingly assuming the role of the oppressor, perpetuating a cycle of gay shame.

It’s possible in saying this, I may be projecting my own internalized gay shame. As someone who was usually the last to be picked for any school team, I’ve grown especially sensitive to situations that drive home old beliefs in my being deficient in “masculinity”.

But even if I wasn’t merely indulging my insecurities, I was certainly within my rights to be hurt by how I was treated, and how I saw others being treated.

This left me with two choices: either remain in the league and try to ignore the toxicity or quit a potentially shame-triggering situation.

Then again, quitting hardly guaranteed complete freedom from the contempt of other gay men.

Self-compassion heals gay shame

When faced with feelings of shame, inadequacy, and inferiority, we adopt one of three tactics: we don the armor of grandiosity as compensation, we crumple, or we employ self-compassion.

To quote eighth century Indian Buddhist monk Shantideva:

Where would there be leather enough to cover the entire world? With just the leather of my sandals, it is as if the whole world were covered. Likewise, I am unable to restrain external phenomena, but I shall restrain my own mind. What need is there to restrain anything else?

Thus, rather than attempting to soften all the world’s painful surfaces, we would be better served by accepting the sensitivity of our figurative feet and finding more practical ways of protecting them.

We do this firstly through self-compassionate inquiry. In the words of Buddhist Pema Chödrön, if we are to attain a new, more empowering view of our suffering, we must embark upon “a process of acknowledging our aversions and our cravings”,

(becoming) familiar with the strategies and beliefs we use to build the walls: What are the stories I tell myself? What repels me and what attracts me? … We can observe ourselves with humor, not getting overly serious, moralistic, or uptight about this investigation.

Having put a name to what I was feeling in the dodgeball league, I was now able to pay attention to the script it was activating and to query its accuracy.

Hardening into anger, or adopting rigid convictions about other people would not serve me. What then was the alternative?

By abandoning my fixed conception of reality, of right and wrong, by leaning into the discomfort, I could learn to be truly present with my own feelings about the situation.

Being present enabled me in turn to self-soothe, an action Self-Compassion author Kristin Neff says is crucial to the process of healing.

The peace of mind ultimately arrived at was a natural outgrowth of such self-compassion. In my case, that transition was facilitated with the guidance and insights of a therapist.

Using kindness and humor to defeat shame

Pema Chödrön’s suggestion of employing humor when investigating your own patterns of thinking can be particularly helpful, at least where shame is concerned.

Humor can help dissolve armor and deflate puffed-up defenses. But humor is only possible once we learn to recognize our cognitive and behavioral scripts as they are being activated.

Confronted by subtle and oftentimes not-so-subtle expressions of contempt from other dodgeball players, my instinct was either flee or fight.

On one hand, they could be viewed as reasonable coping strategies. But on the other, they offered no true grounding against these perceived threats. What was required here was the development of resiliency: the ability to tolerate, rather than avoid, adversity.

So I began to actively laugh off my own mistakes, gently poking fun at other’s egotism or aggression, while striving to show others the generosity of spirit I’d witnessed in the more seasoned players.

In cultivating inward and outward kindness, I found myself forging friendships with other players that served as a bulwark against the toxicity surrounding us.

When I eventually decided to quit the league six months later, it was motivated not by anger or hurt over the conduct of others, but by an on-court injury.

This accident aside, looking back, I realized my decision to remain in the league was a kind of victory. No – I hadn’t mastered the game. And no – the demons of childhood past remained.

Rather, what I had achieved was the greatest freedom that a person can desire. Namely, the freedom of learning to let go.

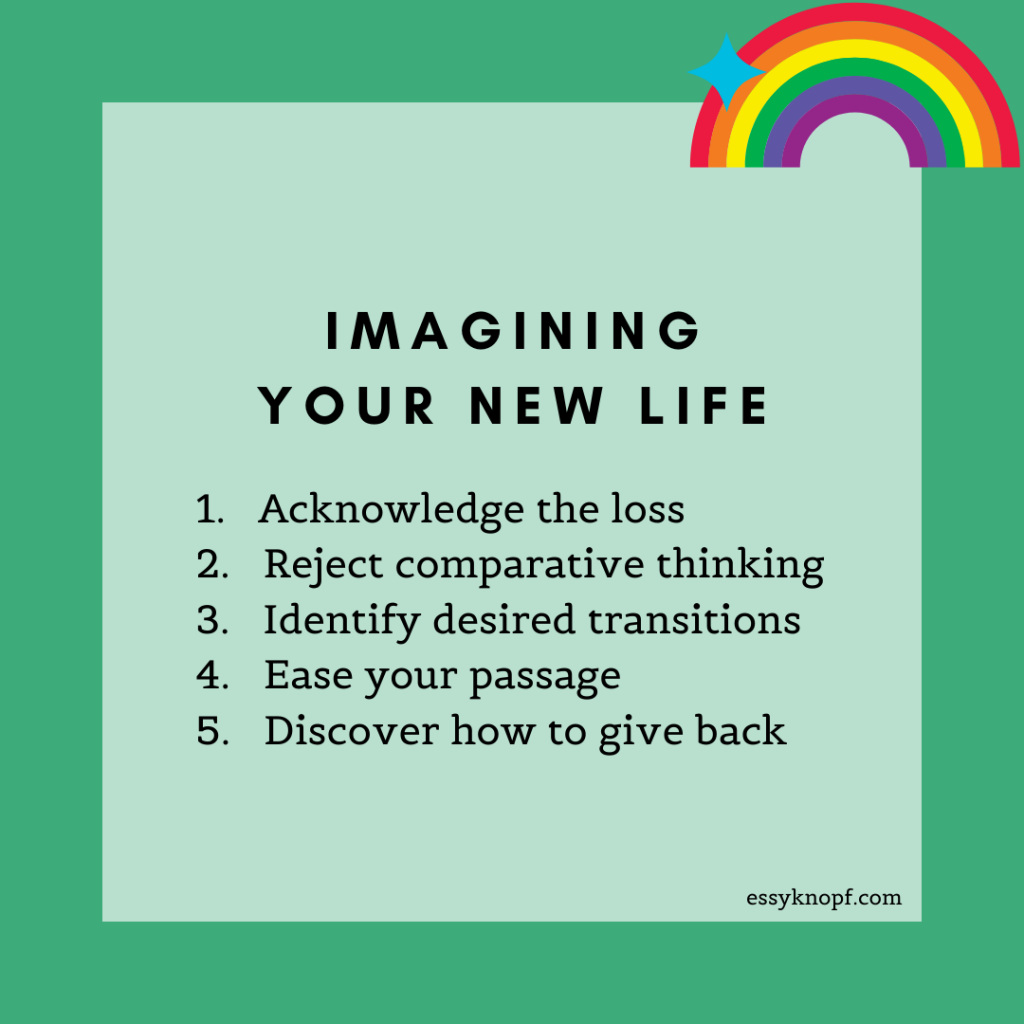

Takeaways

- Identify “shame scripts”.

- Practice self-compassion.

- Use kindness and humor.

Essy Knopf is a therapist who likes to explore what it means to be neurodivergent and queer. Subscribe to get all new posts sent directly to your inbox.