Don’t avoid social mistakes as a neurodivergent. Lean into them.

Neurodivergent (ND) hypervigilance—that is, always being on the lookout for danger—involves the careful observation of neurotypicals (NTs) in an attempt to appease or minimize their negative reactions.

It’s a common response to having to navigate social interactions with NTs; interactions governed by complex and unspoken rules.

Should we fail to follow these rules—inevitable, given they’re never directly explained to NDs—we’re often punished.

NTs may label our remarks and behavior as odd, tangential, patronizing, confusing, incomprehensible, inappropriate, or excessive.

They’ll tell us we came off harsh or insensitive or that we’re being too critical. They may even accuse us of playing dumb or showing off.

Misunderstandings such as these however are not solely the responsibility of the ND. NTs also play a part, as has been argued by researchers who support the double empathy problem theory.

And yet the blame more often than not gets laid at the ND’s door. Blame however does not teach skills. Rather, it imbues NDs with an unhealthy paranoia.

So much so that we end up spending our days watching every little thing we say and do, for fear we might unwittingly offend someone.

Living in shame-prone cultures

This paranoia is a direct product of the fact we live in what author Brené Brown calls a “shame-prone” culture.

In “shame-resilient” cultures, Brown argues, self-worth is unconditional, thereby enabling us “to be vulnerable, share openly, and persevere”.1

In shame-prone cultures, however, leaders and other authority figures “consciously or unconsciously encourage people to connect their self-worth to what they produce”.

This link between self-worth and productivity stems largely from capitalism, and drives people to behave in ways that are “small, resentful, and afraid”.

A classic example of this is the NT preemptively defending themselves or their position, retaliating against a perceived assault with an accusation or criticism, or cutting off communication with the ND.

The legacy of living in shame-prone culture is that we all carry around with us some measure of internalized shame that is automatically triggered when we feel our worthiness has been called into question.

The NT’s hostile response to the ND serves not only to fend off a perceived attack but to deny the implication that they were somehow deserving of this attack in the first place.

In such instances, the NT has failed to give the ND grace; to entertain the possibility of a misunderstanding, ask clarifying questions, and work to repair the social rupture.

The shame of ableism

When NTs respond this way, they may in turn trigger the ND’s own hoard of internalized shame.

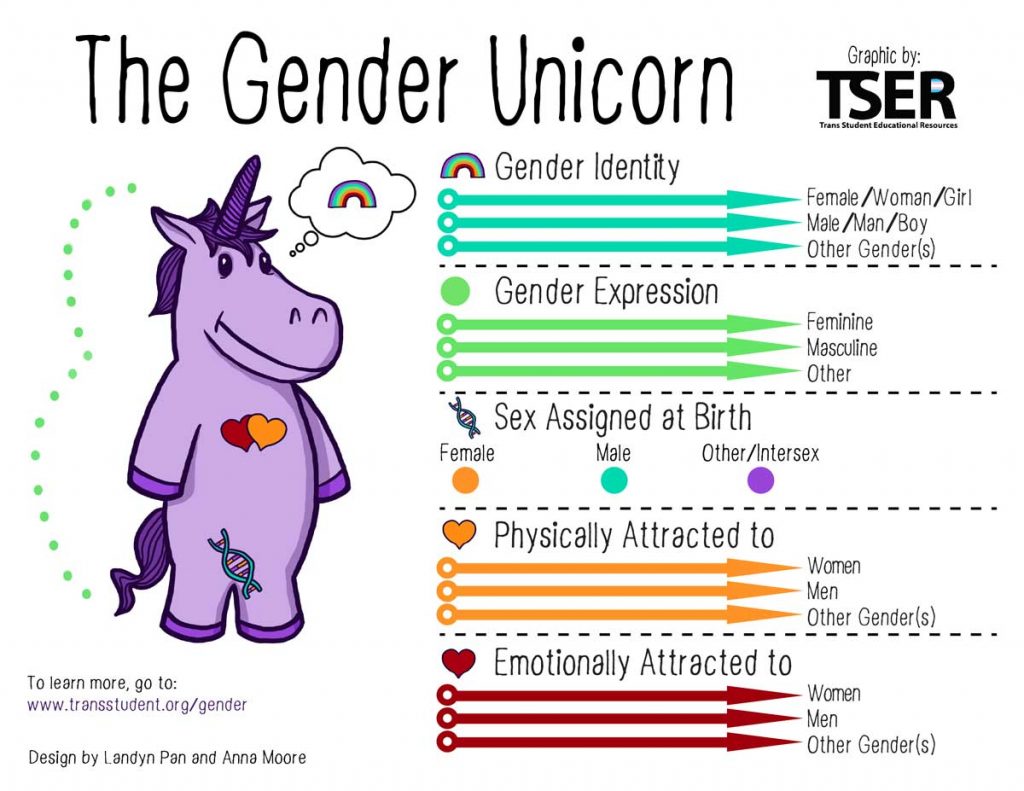

The source of this shame isn’t just that we also live in shame-prone societies, but that these societies are ableist and privilege NTs while oppressing the neurodiverse.

What follows often is a descent down a spiral of self-guilt-tripping. We tell ourselves that we’re “stupid”, “inferior”, “unlikeable”, “terrible company”, and “always messing things up” because that is the message we are routinely sent by NTs.

But unless we are provided constructive opportunities to build and hone our social skills, free of criticism and judgment, we’re likely to continue making mistakes and spiraling ever deeper into shame.

When fight-or-flight goes awry

When our shame is triggered, the ND may similarly marshall their own defenses, launch a counterattack or flee.

NTs and NDs who react in such a fashion are experiencing a “fight-or-flight” response. As The Happiness Trap author Russ Harris explains:

The fight-or-flight response is a primitive survival reflex that originates in the midbrain. It has evolved on the basis that if something is threatening you, your best chance of survival is either to run away (flight) or to stand your ground and defend yourself (fight)… So whenever we perceive a threat, the fight-or-flight response immediately activates. In prehistoric times, this response was lifesaving.2

Fight-or-flight may be an ingrained evolutionary response, but it is also exacerbated by shame-prone cultures, which provide narratives justifying our reactions.

Given the comparatively safe conditions in which many modern humans now live, the fight-or-flight response today is more maladaptive than adaptive.

Why? Because when it is engaged, it can lead to us developing unpleasant feelings. It results in the negative reactions detailed above, usually with destructive results.

Neurodivergent social challenges

Misunderstandings between NDs and NTs largely occur because of inherent differences in cognitive and social styles.

Autistics as a population for example have been found to exhibit egocentric (self) bias, as opposed to altercentric (other) bias when it comes to social interactions.3

That is, we tend to ascribe our feelings, thoughts, or needs to others, rather than intuiting, reading, or asking.

This tendency may result in part from developmental prosopagnosia, which is more common among autistic individuals.4

Developmental prosopagnosia refers to impaired face identity and facial expressions recognition, a skill that is essential for correctly gauging others’ emotions and intentions.5

These differences leave autistics less capable of realizing we have made a social blunder, which can in turn make the task of overcoming them appear almost impossible.

The downside of ND hypervigilance

Accidents and misunderstandings are par for the course when interacting with NTs, and the most we can ever do as NDs is to proceed with caution.

Taken to its extreme, caution can become ND hypervigilance, as we work to compensate for perceived threats with strategies such as masking.6 Hypervigilance and compensatory strategies are common resorts for the overly-conscientious NDs.

For years, I myself employed hypervigilance, scanning strangers during social interactions for friend/foe signals, subjecting every conversation to extensive analysis.

Hours were spent trying to decipher the meaning behind a particular facial expression or a specific choice of word as if doing so might protect me against future mistakes.

And yet for all this effort, I continued to put my foot wrong, with NTs often distancing themselves from me despite my attempts to explain myself or apologize.

ND hypervigilance is what happens when fear monopolizes our psyche. It leaves us frozen; incapable of feeling and expressing our emotions; unable to engage in spontaneity, jokes, and laughter.

Such expressions can’t happen without vulnerability, and to be vulnerable in a hostile social environment is to open oneself to attack.

To remain in a hypervigilant state, however, constitutes a complete betrayal of both ourselves and our needs. It puts the onus on us to do whatever possible to ensure our social interactions are successful—an expectation no one can reasonably meet.

And it deprives others of the opportunity to get to know our authentic ND selves.

Empathy as an alternative to ND hypervigilance

As discussed in a previous post, modulation—selective and strategic presentation of the self—is a practice all individuals engage in during everyday interactions. It is key to generating social harmony and cohesion.

Modulation as a practice is highly advantageous to NDs. It is not a compensatory behavior, not an attempt at appeasement, but rather concerned with meeting the other person where they’re at.

Social interactions, whether they involve Nds or NTs, are a dance that must be navigated carefully, patiently, and kindly. Both partners must regularly check in with each other to ensure the other party is doing okay.

Ruptures in these relationships happen when:

- We don’t ask our partner’s permission before initiating the dance

- We insist on not following the tempo of the music

- We fail to match our partner’s pace or to coordinate our steps with theirs

- We step on our partner’s toes—and don’t apologize

The good news is that these ruptures can be repaired through acts of consideration, kindness, and empathy.

Openness and vulnerability: the way forward

NDs need not live in a perpetual crouch, terrified of negative consequences when we commit a social mistake.

Rather, we can approach these ruptures with an attitude of openness. When others offer complaints or requests, we have the option to listen without immediately reacting.

If someone shares that they have been genuinely hurt or harmed by something we’ve said or done, we can create a space for their feelings, without taking them on, while braving any discomfort that might result.

We can lean into our mistakes by acknowledging, apologizing, and pledging to do better—while also asking the other person’s advice, when appropriate, on how we might do so.

As someone who is both autistic and ADHD, I have found that interpersonal conflict rarely continues if I admit my errors soon after they are brought to my attention.

For those of us with a history of being criticized during past social interactions with NTs, such an admission might not come easy. But if we are to triumph over our internalized shame, we must be willing to reach for self-compassion.

Practicing self-compassion means choosing to accept our fallibility and to love ourselves regardless. It means embracing our vulnerability and having “the courage to show up and be seen when we have no control over the outcome”.7

Steps to overcome ND hypervigilance

Vulnerability is a key ingredient for empathy, an approach that forms the basis of all solutions I will propose to common ND social challenges.

These solutions typically involve one or more of the following actions:

- Assessing needs

- Asking permission

- Seeking clarification

- Listening reflectively

- Admitting mistakes

- Sharing intentions

- Adjusting behaviors

I share my approach here with the caveat that these actions are not exclusively for ND folks.

NTs are equally capable of making mistakes and equally responsible for taking action when it is brought to their attention. The fact that many choose not to, instead of pinning blame exclusively on the ND for a misunderstanding, is a reflection of neurotypical privilege.

It’s perfectly fair to expect NTs to practice the actions I’ve listed above. Arguably, ND hypervigilance wouldn’t be necessary at all, if NTs indeed did so.

But, as in any social interaction, we should strive to focus on only that which is within our control. Namely: whether or not we choose to take the high road, and the rigor with which we apply ourselves to this effort.

Essy Knopf is a therapist who likes to explore what it means to be neurodivergent and queer. Subscribe to get all new posts sent directly to your inbox.