‘Breadcrumbing’: the gay dating app practice that destroys connection

If you’ve ever used a gay dating app before, you’ve likely experienced “flash in the pan” conversations that start and end abruptly, usually without explanation.

Turns out that the sudden appearance, followed by the sudden disappearance, of chat partners is often part of an intentional strategy known as “breadcrumbing”.

Prior to learning this term, I liked to refer to my experiences using a phrase of my own invention, the “sushi train effect”.

If you’ve ever attended a sushi train restaurant, you can probably already see the comparison I’m making. For those of you who haven’t, allow me to explain.

The sushi train effect explained

At sushi train restaurants, fresh-made dishes are presented on small plates delivered using a circular conveyor belt, or the back of a toy train that follows a loop.

Many usual favorites can be obtained via this method—everything from tempura to nigiri and uramaki rolls, dumplings, and more.

Diners choose the dishes they want to eat then remove them from the belt/train. As they do, sushi chefs prepare new dishes to replenish the train’s stock with.

The effect is like sitting before a buffet—or rather, a never-ending supply of snack-sized meals.

When one logs onto a gay dating app, one’s profile is immediately presented for review by other users, much like a new dish appearing on a sushi train.

On apps like Grindr or Scruff, that image appears in a grid of other profile images, organized according to current proximity.

If it’s your first time using the app, or simply your first time using that particular image, your profile will exude an aura of novelty. A feeding frenzy will ensue, with other users flooding your account with messages.

These users may express keen interest in, and admiration for, your person, replying to you with an urgency that demands immediate engagement.

‘Boom and bust’ on the gay dating app

If you reply, many of these interactions may end then and there, with the other user mysteriously withdrawing the instant they’ve obtained your attention.

But if you delay your reply, you can often expect the other user—who has subsequently logged off—to reappear sometime later, offering what usually amounts to a lukewarm response.

Their interest, as it turns out, was only temporary, even opportunistic. A brief window opened, offering a tantalizing glimpse of a world of possibility, then swiftly closed.

One is thus given the impression that others’ availability is time-limited, and even then when you do manage to catch them on the app, there is often no tangible outcome.

Recipients of this sudden influx of attention may be left wondering if what they have experienced is not admiration, but a Pavlovian response—like the salivating of dogs at the sound of the bell.

This is the first part of the “sushi train effect”: idolization by total strangers. The second part is devaluation.

As the aura of novelty fades, what begins as a flood will inevitably slow to a trickle. This can happen over the course of a day, or even a few hours.

Before one was treated as “hot property”, but now one is regarded as a bottom-of-the-barrel fixer-upper. One’s face or torso, once distinguishable from countless others, becomes just another brick in the wall.

Like any dish glimpsed by diners circling the sushi train one too many times, one’s profile loses appeal through sheer familiarity.

This meteoric rise, followed by a precipitous decline, creates an impression of “boom and bust” that can leave most app users feeling rather disoriented.

One moment, one feels seen and valued, and the next, it’s as if one has been discarded; reduced to yet another piece of flotsam floating in the modern dating and hookup sea.

‘The sushi train effect’ as a form of ‘breadcrumbing’

The third part of the sushi train effect is delayed revaluation.

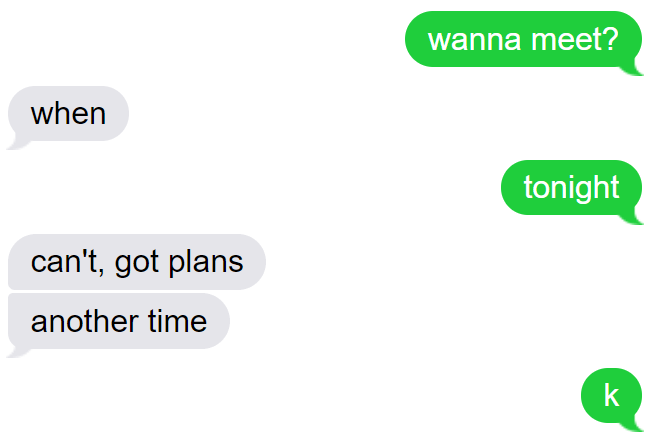

Take for example the user who declares their interest in you and agrees to meet in person, but who—when pressed for specifics—fails to follow through.

Sometimes, they turn on a dime, it feels like you’re chatting with a completely different person, one who now believes you are completely unworthy of the effort.

Other times, they may agree, only to cancel the meetup, citing some unforeseen event or complication. They may also indefinitely “bench” it, but without proposing a suitable date or time. Or they may block your account outright.

Then, days, weeks, months, or even years later, this individual will reach out again—prompted, it seems, by your convenient reappearance in their dating or hookup app grid.

They may offer an explanation for their disappearance, maybe even an apology for having flaked on you. Or they may simply pretend it never happened.

What’s most confusing is when this person expresses the same level of interest they did on the first occasion.

If you remember their sending mixed messages, you may feel tempted to address this directly. The alternative after all is silence, and merely contenting yourself with this sudden attention.

Should you do this, you may become caught up in an amnesiac dance, make-believing it was circumstance and not a conscious choice that prevented your meeting the first time around.

The hardened skeptics among us however will throw the stranger’s sincerity into doubt, concluding that they’re messaging again out of pure boredom.

And a lot of the time, we are justified in this belief. Many app users are merely hunting for attention, like an addict hunting for their next fix. Their interest has less to do with us as people and more with the renewed novelty we represent.

To return to the sushi train analogy: dishes once declared ho-hum are often reappraised by diners after a long absence, and may thus regain some of their former appeal.

Turns out this behavior isn’t exclusive to gay dating and hookup apps but is rampant in the wider dating world.

‘Breadcrumbing’ explained

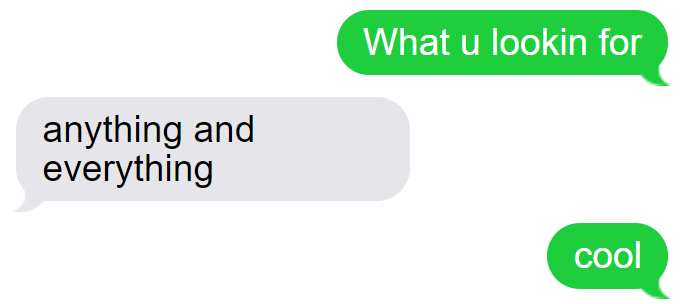

“Breadcrumbing” is when a dater uses small amounts of attention or validation to keep you interested in them. Basically, what it usually boils down to is fishing for attention.

Daters typically leave “breadcrumbs” when they aren’t seriously interested in meeting. What does “breadcrumbing” commonly look like on a gay dating app?

Microcommunication is a common example: users who repeatedly check in (“Hey”/”How are you?”/”What you up to?”), exchange brief pleasantries, but make no serious effort to sustain a mutual conversation.

Sudden disappearances, followed by sudden reappearances—much in the same fashion I’ve described above.

Small talk that goes nowhere. Breadcrumbers use small talk to sustain the interaction, even when they have no intention to take that interaction offline.

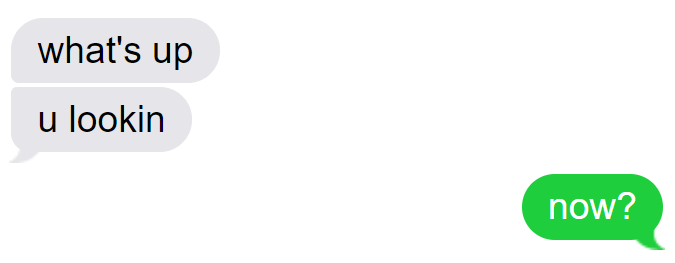

Refusing to schedule dates. Breadcrumbers are usually reluctant to make any kind of commitment, as their main purpose in messaging is to secure attention or validation.

Trying to set up a date is the quickest way to suss out a breadcrumber’s intention, as they will usually evade, make an excuse, or bail beforehand.

Refusing to follow through with plans. As noted, breadcrumbers refuse to meet in person, preferring instead the minimal effort involved in a text exchange.

In short, breadcrumbers like to talk a big game but will always balk, for various reasons.

Some may feel lonely, bored, and/or insecure and are seeking a quick boost to their self-esteem. In such instances, breadcrumbers receive your responses as proof of their attractiveness or worth.

Alternatively, the breadcrumber may want contact with other gay men, but see face-to-face meetings as carrying risks or responsibilities they aren’t prepared to deal with.

There are also breadcrumbers who are driven by a narcissistic desire they know they can meet by sustaining text banter with multiple suitors, often at the same time.

Whatever their motives, know that unless you yourself are using dating and hookup apps to breadcrumb, you’re likely to find these kinds of interactions to be unsatisfying and, ultimately, a waste of time.

Breadcrumbers are enabled by gay dating app design

Breadcrumbing is enabled by app design that reinforces this behavior while failing to hold those accountable responsible.

App makers are profit-driven, and in order to increase their profit, they need users to remain on their platforms as long as possible. Previously, I’ve referred to this phenomenon as “distraction capitalism”.

It follows therefore that these makers are willing to use all manner of tactics to guarantee this outcome. This includes refusing to set specific parameters for accessing and using the app.

The problem with parameters—in the eyes of app makers’, anyways—is that they automatically screen out a significant segment of the user base. Monitoring problematic user behavior also requires hiring dedicated staff and thus comes with undesirable overhead.

So like many other apps or web-based services, the designers opt instead for a more hands-off, almost-anything-goes kind of approach.

Another tactic used by app makers is gamification. I’ve talked about it before, but I’ll provide a quick recap here.

Gamification involves using positive reinforcement to reinforce users’ continued use, for example, through instant notifications, chimes, and flashy animations.

All of these stimuli are carefully calibrated to trigger neurochemical activity associated with success.

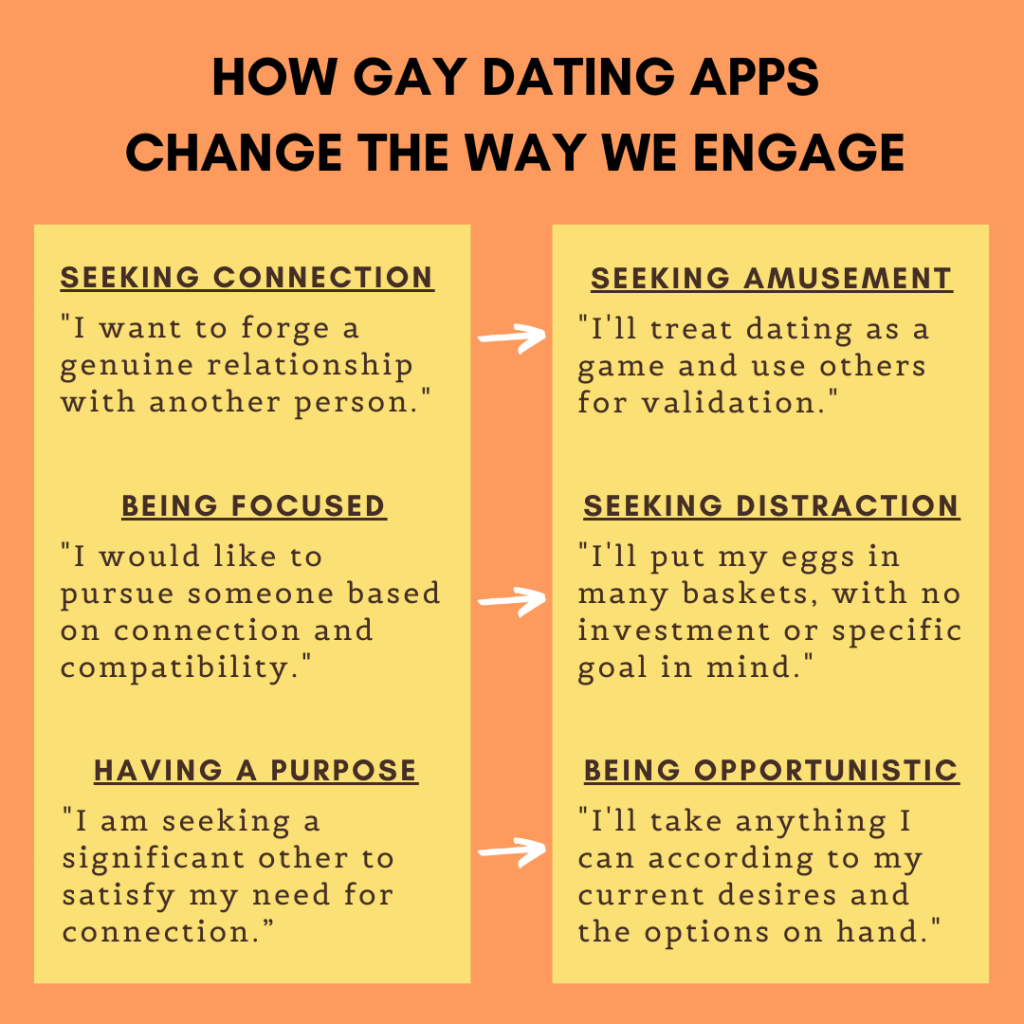

Gay dating app gamification thus doesn’t just trivialize human interactions—it frames interactions as opportunities to maximize the number of responses they receive, and therefore validation gained from others.

Taken to the extreme, this results in some users treating their fellows like human PEZ dispensers, whose only purpose is to disgorge attention upon demand.

Thus, when app makers prioritize the bottom line, they are willfully facilitating this kind of attentional exploitation. They are enabling breadcrumbing.

Users may thus find themselves caught in a perpetual loop of short-lived banter that never deepens into a lasting connection.

Interactions come to resemble busywork, leaving those seeking something more substantive out in the cold.

Until app makers start using design to create a culture that promotes healthy interactions, those of us pursuing meaningful interactions would be better off spending our time elsewhere.

If you’re seeking some tips on how you can step away from gay dating apps, I’ve got you covered.

Essy Knopf is a therapist who likes to explore what it means to be neurodivergent and queer. Subscribe to get all new posts sent directly to your inbox.