Anxious Seeks Canine – Part 18: ‘It’s not his fault’

Anxious Seeks Canine is a memoir blog series about a gay man living with Asperger’s, mental illness, and the relationships that may very well be fueling it. Names and identifying details have been changed to protect the privacy of all featured individuals. Except for the dog. Here’s part 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, and 18. Subscribe for more posts.

I

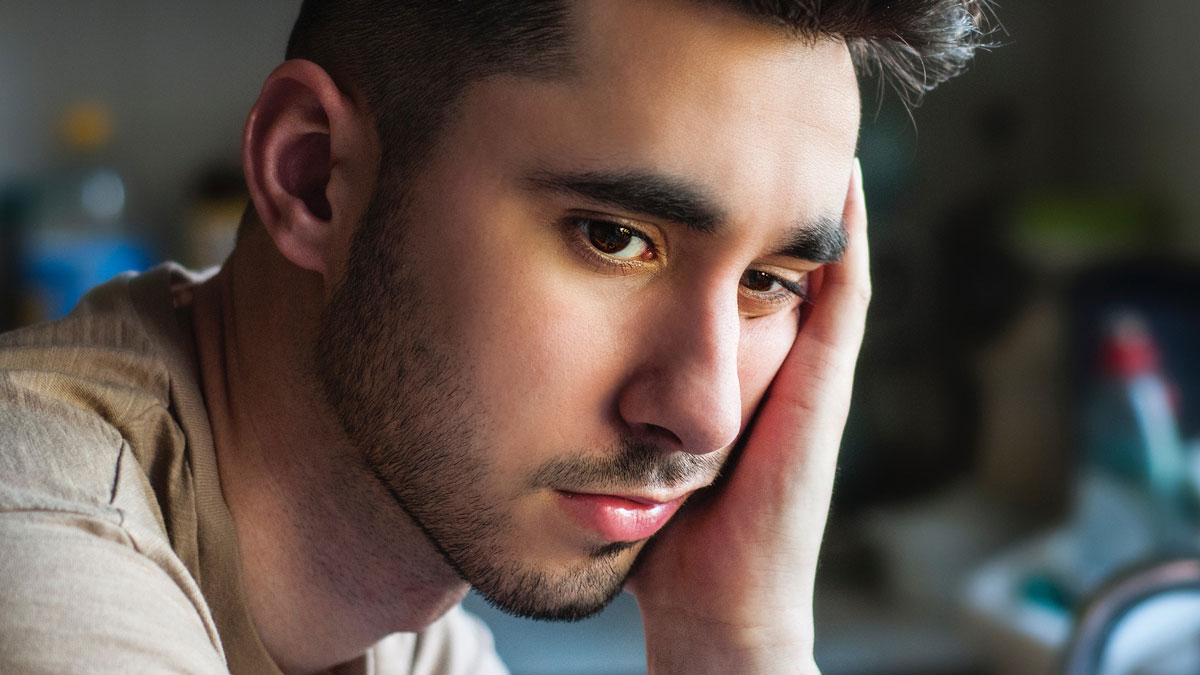

“I guess I am wondering,” Dr. Ihekweme began, “if you were biting off more than you could chew?”

My head dipped in a grudging nod.

The first time I had tried meditation, I’d sat for a whole 45 minutes, ramrod straight…but wriggling all the same.

“It seemed pretty reasonable at the time,” I bleated.

“Maybe,” Dr. Ihekweme began, “you could try 15 or 20 instead? Just to start with.”

“Don’t you understand?” I wanted to cry. “That would be conceding defeat!”

My perfectionism after all refused to settle for anything short of, well, perfect.

My phone buzzed on the sofa cushion beside me. Glancing down, I saw a photo appear of Cash on some leafy path, mid-walk. He looked, dare I say, happy.

“Sorry,” I said, brandishing the phone for my therapist’s benefit. “It’s Cash’s new owner.”

“Everything okay?” Dr. Ihekweme asked.

“I think so,” I offered.

One week on from his re-adoption, Cash’s old/new owner Anja had reassured me that he was settling in just fine. To believe otherwise, of course, meant prodding a hornet’s nest of dormant guilt.

“I guess you’re right,” I eventually signed. “Forty-five minutes is kind of extreme.”

“Have you thought about doing a guided session?”

“Audio tracks almost always put me to sleep.” Dr. Ihekweme mulled over this, then got up to fish around in his desk drawer.

“Normally I would not do this,” he said, “but in your case, I would like to make a recommendation.”

My therapist brought out a bundle of papers.

“I want you to try this meditation course,” he said, peeling off a pamphlet and offering it to me. “It’s subscription-based, you pay once and they’ll send you a new lesson in the mail every week for a year.”

For the first time since starting treatment, I found myself questioning Dr. Ihekweme’s judgment. The most guided meditations required were an attentional sliver…and yet still I struggled.

And now my therapist was suggesting I take an entire course?

Fending off incredulity, I studied the pamphlet, bracing myself for the spoiled-milk whiff of a pyramid scheme.

“This course will help you build a meditation practice step by step,” Dr. Ihekweme explained. “You choose the pace.”

“You’ve done it already? The course, I mean.”

“I’ve been following these classes for years,” Dr. Ihekweme confessed.

“And do they work?” He grinned at bluntness of my question.

“Do they work? Well, let’s just days that some days I wake up in a state of joy and gratitude.”

A state of joy and gratitude? It was almost enough to make me dry-retch.

But given I was handing cash over to my therapist week in and week out, the very least I could do was take a recommendation.

II

The pamphlet remained tucked in my jacket pocket, temporarily forgotten, for some days afterward.

When I dug it out again, it was less out of a sense of obligation than out of growing desperation.

Even with Cash gone, my stress levels remained as high as ever. Whatever I had been doing so far to manage it, it clearly was not working.

Suspending my skepticism, I paid a nominal fee and signed up for a year’s worth of lessons.

A few weeks later I clawed back my commitments and peeled open a newly arrived booklet. What I found inside were refreshingly simple instructions, couched in beautiful anecdotes and symbolism.

When the second packet arrived in the mail a short while later, I devoured its contents in under an hour.

By the third lesson, I’d gone from eye-rolling cynic to Kool-Aid zealot, from 15-minute daily meditation sessions to 30-minute sessions three times a day.

The depression receded, replaced first by a vague sense of wellbeing, then instances of boundless optimism.

With Dr. Ihekweme’s guidance, I found myself more and more able to achieve a birds-eye view of my own suffering.

The inner critic who had presided, despot-like, over my life, was now being shown the door. And as his hold on me loosened, so too did mine on the metastasizing perfectionism and workaholism that had long propped up my self-worth.

This is not to imply, of course, that either completely went away. Rather, they lingered like Cash’s carpet stains: unsightly – but valuable – reminders.

Left unchecked, mental illness had twined its creepers around my thoughts, thrusting its roots into the bedrock of my personhood.

But where I had once lived in terror that I might not ever be able to extricate myself, I was slowly accepting that, one way or another, I was going to be okay.

The deciding factor of okayness, being – of all things – my willingness to accept its possibility; to let the vessel of my being calmly ride the peaks and troughs of life’s uncertain seas.

For years I had shambled through life, dragging shame and despair in my wake like a ball and chain.

Yet in learning to offer myself the acknowledgment, the affirmation, the acceptance I had been denied, I was suddenly able to shuck the toxic, constricting narratives of my past like an outgrown skin.

III

But smooth sailing was no more a guarantee for me than it was for Cash. About a month after his rehoming, Anja called in a state of exasperation.

“He’s just too needy,” she said. “He’s constantly underfoot. He refuses to be separated from me. And he barks at every visitor!”

“You’re telling me,” I wanted to say, but I held my tongue.

“I know it’s not his fault,” Anja continued, “but I can’t help but feel angry at him.”

Anja’s litany of complaints mirrored my own, and yet I was still surprised. Surely her prior experience with Cash surely should have told her what she was in for.

Even with all her years’ experience as a dog owner, Anja had not felt prepared for the stifling possessiveness that had followed Cash’s re-adoption.

“… Do you know anyone who might want him?” she asked.

And there it was. My decision to rehome Cash had ended in disaster.

Where before I had suggested visiting Anja to see Cash, I found myself now putting these plans on hold. Seeing me again could create false expectations.

Offering to temporarily house Cash until a suitable replacement owner had been located thus was out of the question.

The best option available now was to do what I had previously refused to: return Cash to the adoption agency.

Days after Anja dropped him off, I got a call from an employee.

“We just want to know why you didn’t return Cash to us directly,” she said, her voice a few degrees south of zero.

The woman clearly didn’t understand what I did: that the return window had long since closed.

Crude as this analogy might seem, having refused to return Cash while he was still within some imaginary warranty period, what right had I do so now?

Still, I humored the inquiry, even offering to send the woman my three-page guide. Radio silence followed, all my emails to the agency about Cash’s wellbeing going unanswered.

The hammer of judgment, it seemed, had fallen, and I charged in absentia with dereliction of duty.

And so what. Only I knew the lengths to which I had gone. No explanation was demanded, nor needed.

The best I could hope for now was that my erstwhile pet was this much closer to finding his forever home.

IV

The day I’d adopted Cash, the agency had given me a framed photograph of the two of us posing in front of their office.

The photographer had captured me holding a somewhat confused-looking Cash in a half-hug, less an act of spontaneous affection than an attempt to stop him running away.

At the time, I saw this photo as a promise of future happiness. Only later would I recognize it as an ultimate representation of the anxiety that tainted our relationship.

Up until the day I’d surrendered Cash, that photo had rested on my mantelpiece. Unable to deal with the feelings it evoked, I had packed it and every other reminder of our time together away.

Half a year later, post-knee-surgery, I found myself digging under my bed and rediscovering the box of forbidden mementos: a dirty leash, a gnawed chew toy, a polka dot dress.

And I found myself wondering, did Cash still remember me? Did he think of me with sadness, as I often did him? Or with joy?

As with my ex Derrick before, I had found myself grieving the relationship well before the official end date. My rocky passage through denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance might have been avoided completely, had I found a surefire treatment for Cash’s anxiety.

Shoulda coulda woulda. The grief resurged then, but it was not bottomless, nor as complicated by doubt as I had expected.

Sometimes when entering a room, I had found my dog sprawled on his back, feet in the air, the very picture of a poisoning victim.

My first thought would be a tongue-in-cheek: “Finally, the little nuisance is dead”. But of course, he would just be sleeping, as he often did, contorted like some figure in a Picasso painting.

Later I would look back at photos of him in these various positions and laugh at the ridiculousness of it all. Then I would miss him; miss how he would jut his snout out from beneath the desk, peering up at me in a silent request to “sit on daddy, please”.

What I did not miss, however, was the incessant barking, the separation anxiety, and the clashes with other dogs. Remembering these traits was like having someone hold smelling salts to my nose.

In a hot second, I’d go from the dreamy recollection to bolt upright and sober. Off came the rose-tinted spectacles, and down the heel of practicality, sending little pieces of nostalgia-glass flying.

As time went by, I found myself swinging less and less between these poles, settling instead on a comfortable in-between.

It was quite possible, I realized, to both miss something and be relieved by its absence. Entertaining both feelings did not necessarily mean I had to be engulfed – or condemned – by them.

Parting ways with Cash at the time had not been a bad decision. In fact, it had seemed the only decision.

Too caught up in my own dysfunction, I had been in no position to address Cash’s own. As time went by, it had become apparent that the question was not how I was failing him, but rather how I was failing myself.

When I removed the box from under my bed, I discovered two other things that I had, until now, forgotten about entirely.

The first was a whiteboard, caked with dust, carpet fluff, and dog hair.

On it was scrawled a list of dreams and goals, most of which had been either scraped or wiped off during its passage out of Derrick’s storage shed.

Of the few items that remained, one stood out: “Relax and give yourself time to just ‘be’.”

For a year-and-a-half, I had aspired to a happier, more wholesome life. Instead, I’d found distraction, endured loss, and sought release.

Now, I had returned to that same aspiration, the whiteboard sitting before me posing an open challenge.

But there was the second item besides the whiteboard still to consider: Cash’s anxiety vest.

What had motivated me to first buy it was evidence that the deep pressure such vests provided could soothe anxious canines. The same principle had also applied to humans.

But buying Cash his vest, it had never occurred to me that all along I might have been equally served by wearing one.

Opening a browser tab, I hootfooted it over to Amazon, and minutes later had a human-sized compression vest on order.

The similarities that first drew Cash and I together may have ultimately forced us apart. But they also brought into focus the irony of my intentions: namely, that the help I’d tried to give my dog was ultimately the help I myself had most needed.

This post concludes Anxious Seeks Canine.

Essy Knopf is a therapist who likes to explore what it means to be neurodivergent and queer. Subscribe to get all new posts sent directly to your inbox.