Don’t shoot yourself in the foot. Here’s how to be a better social justice warrior online

The term “social justice warriors” should mean advocates for progressive causes. Internet trolls however have tried to paint SJWs as social media “slacktivists” and political correctness police.

There may be an element of truth to this. We may not all be keyboard warriors ready to hold every wrongdoer to account, but many of us still use these platforms for activism, consciousness-raising, and community organization.

Social media in particular has empowered many marginalized individuals to challenge dominant narratives perpetuated by mass media and the oppressive systems they serve.1234

But when we threaten the status quo, we also threaten the privileged few it has long served. Given trolls themselves are typically members of these empowered groups—White males with a “certain degree of economic privilege”5—it’s no wonder they can be such tough critics.

Whether we are calling out ableism on Twitter or criticizing microaggressions on YouTube (here’s a handy guide to SJW terminology), it’s important that we always hold ourselves to a higher standard.

By this, I mean that we remember our goal is as much interrupting oppression as it is inspiring individual change.

As social justice warriors, we can help others navigate the process of revising their beliefs and behaviors—but only if we act in a way that does not first alienate or create a toxic “us” vs. “them” mentality.

Table of contents

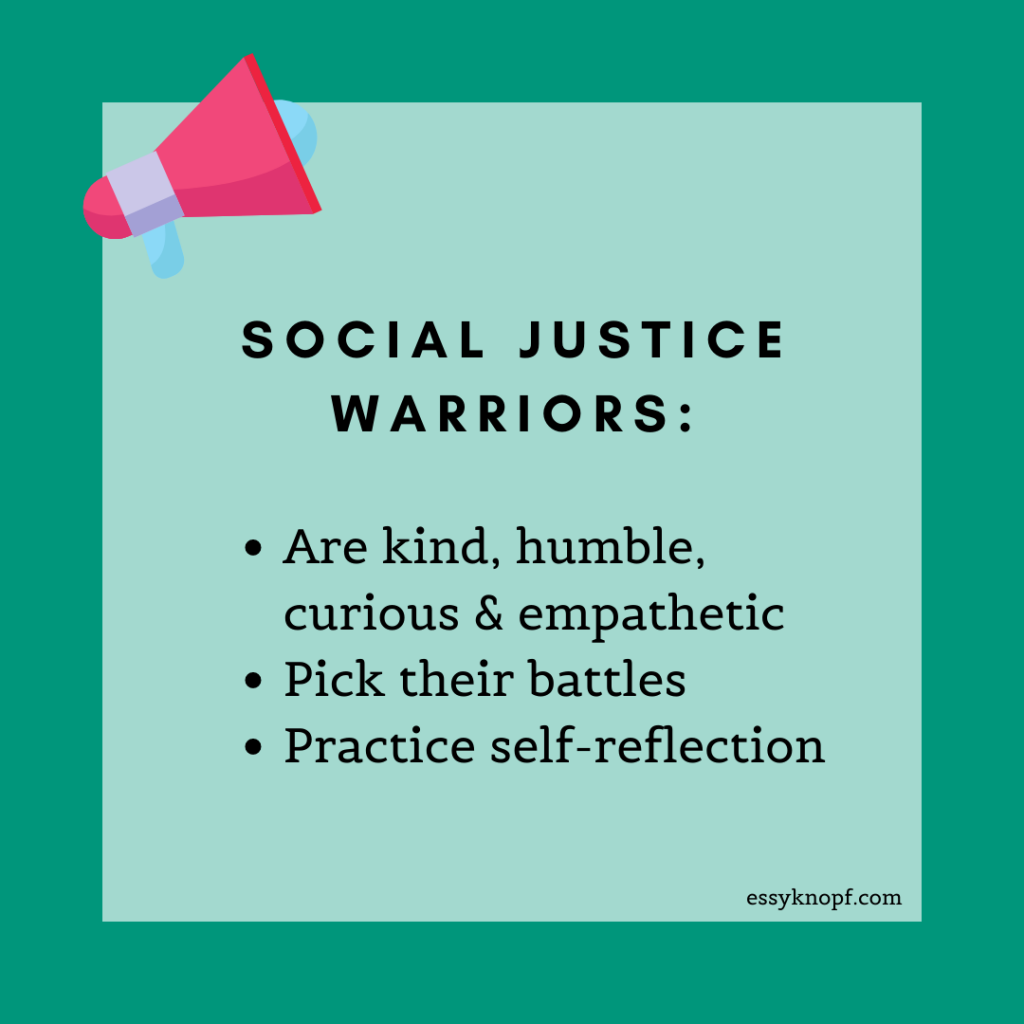

Social justice warriors are kind

When confronted with injustice and oppression, SJWs naturally feel compelled to speak out. The problem starts when we believe that our capacity for critical thinking gives us a license to simply be critical.

If we lean into this belief, we adopt a holier-than-thou attitude. We task ourselves with fighting our many “enemies”, rather than seeing them as potential allies and stakeholders in the change we desire.678

Furthermore, being publicly called out over one’s conduct, whether online or offline usually entails some loss of face.

For me, being corrected over something I have said on the grounds of it being incorrect and/or offensive has—at the very minimum—evoked embarrassment and defensiveness.

There have also been instances where I have found myself on the receiving end of a global attack on my privileges, my conduct, or my character.

These kinds of attacks have the potential to activate what Brené Brown terms “shame tapes”: “the messages of self-doubt and self-criticism that we [all] carry around in our heads”.9

Brown describes shame as the belief that our actions or inactions make us unworthy of love, belonging, or connection. So corrosive is this belief that it can erase our capacity to change.

When it doesn’t lead people to flee, it can cause them to double down, or to go into attack mode.

Where it comes to online advocacy and activism, controversy with civility certainly is possible, and necessary.

Yet no matter how abominable the other person’s point of view or egregious their conduct, we as social justice warriors must remember that another’s capacity to grow can only be tapped so long as they feel respected and safe enough to concede there is room for improvement.

If we are courteous and kind, we create a low-threat environment in which these self-protective mechanisms are not necessary, and transformation is possible.

If we want to achieve any mutual understanding and/or consensus, it behooves us to build bridges, not walls—to borrow the words of Pope Francis.10

Anger over others’ wrongful behavior can be justified, but rarely is anger alone a motivator to change. For us to move forward as a society, we must be willing to forgive.

By forgiveness, I am not suggesting we overlook individual responsibility or accountability. Nor am I proposing we permit or enable oppression.

Rather, I am reminding readers that—to quote Desmund Tutu—”every one of us is both inherently good and inherently flawed. Within every hopeless situation and every seemingly hopeless person lies the possibility of transformation”.11

SJWs are humble

Wise social justice warriors know that when we appoint ourselves the arbitrator of right and wrong, we fail to admit to our fallibility. We forget that we too at some point have been wrong.

For example, derogatory terms regarding people with disabilities are so ingrained in Australian slang that to call something “r******d” or “s*****c” often does not warrant a second thought.

It was only once I was diagnosed with a disability that I came to truly understand how hurtful and oppressive such terms could be.

In the years since I have encountered people for whom the use of these terms was also a product of habit rather than outright maliciousness. Offensive as they have since become for me, I have had to remind myself that I once was no different.

Social justice warriors know that language can be oppressive. A humble SJW however understands that penalizing others over perceived technicalities or semantics does not facilitate dialogue.

Practicing humility also means being willing to front up to our own mistakes, before we expect others to admit to their own. It also means acknowledging we can choose how we react to those of others.

In the words of Holocaust survivor Viktor E. Frankl: “Between stimulus and response, there is a space. In that space lies our freedom and our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our happiness”.12

When we lash out at those who trigger our emotions, we are also missing a valuable opportunity for personal growth.

If taking personal responsibility for our feelings feels impossible, then perhaps it is best we take a step back, reflect, practice self-compassion, and seek the professional support and healing we need.

Remember: feeling aggrieved or believing ourselves to be on the right side of history does not grant us a hall pass to punish, humiliate, antagonize, or bully.

SJWs are curious

Effective social justice warriors know that consciousness-raising does not follow a hypodermic needle model. We don’t simply “inject” information into our audience and expect our lessons to somehow stick.

Rather than brutalizing others with our beliefs, we should aim instead to sensitize them, through rapport- and relationship-building.

Online, this may be difficult. Exchanges tend to be fleeting and sometimes ill-considered. Who here hasn’t once shot from the hip, firing off a furious email or direct message into the ether?

Digital environments remove many of the inhibitions that stop us from otherwise engaging in antisocial behaviors, resulting in a phenomenon known as the Online Disinhibition Effect.

We can see this effect at play when we try to set “wrongdoers” right online, imposing viewpoints and forcing confrontations. As noted already, these behaviors do not nurture empathy. Rather, they feed conflict.

Shifting worldviews requires that we and our dialogue partners unpack the thinking behind them.

Broadminded SJWs recognize that worldviews are a product of valid life experiences and values—values which are not always self-selected but are imposed by “cultural norms, policies, laws, and public opinion”.13

With time and patience, and by getting curious and asking questions, we may be able to help others uncover discrepancies between our dialogue partners’ thoughts and values, generate cognitive dissonance, and, hopefully, action.

SJWs are empathetic

By modeling openness, we create an environment in which empathy can flourish. And to reiterate: unless a baseline of empathy has been first established, a stranger may not be willing to hear all you have to say.

Combining the qualities mentioned above—kindness, mindfulness, humility, and curiosity—can thus increase our chances drastically.

“We should look upon others with respect,” wrote Baháʼí leader ‘Abdu’l-Bahá.

“When attempting to explain and demonstrate, we should speak as if we are investigating the truth. [We] should speak with the utmost kindliness, lowliness, and humility, for such speech exerteth influence and educateth the souls.”14

‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s words are echoed by Buddhist spiritual leader Thich Nhat Hanh, who counsels us to employ “loving speech”.

By speaking in a way that inspires hope, forgiveness, and compassion, and by treating all who cross our paths with understanding and generosity of spirit—whatever their beliefs—we can move towards reconciliation and resolution.15

Nhat Hanh suggests that before trying to change others, we should instead practice “deep listening”:

“Even if [the other person] says things that are full of wrong perceptions, full of bitterness, you are still capable of continuing to listen with compassion. Because you know that listening like that, you give that person a chance to suffer less. If you want to help him to correct his perception, you wait for another time. For now, you don’t interrupt. You don’t argue. If you do, he loses his chance. You just listen with compassion and help him to suffer less. One hour like that can bring transformation and healing.”16

SJWs pick their battles

A wise SJW seeks to clarify intent and meaning, rather than condemning others outright. Automatically presuming bad intent on behalf of our dialogue partner is a one-way ticket to nowhere.

That said, attention-seekers who have no time for respectful dialogue and are only interested in winning debates are best avoided.

Likewise, when confronted by hate speech, the most judicious course of action usually involves blocking and reporting the perpetrators.

As per the aphorism “don’t feed the trolls”, we should avoid such toxic and ultimately futile exchanges, and consider instead engaging in self-care.

To that point, social justice warriors should recognize that some settings are not naturally conducive to meaningful or purposeful dialogue.

For example, when we are interacting with strangers on Twitter, we have no reason to believe our point of view will be acknowledged, respected, and given careful consideration.

Anonymity and the absence of the usual social checks and balances mean that exchanges of opinion on social media can quickly devolve into mud-slinging matches.

And given social media platforms abound with bots and trolls, we may have no way of knowing whether the views put forth in response even belong to a real person.

Which begs the question: what is your goal in initiating or continuing an interaction online? What do you hope to achieve by challenging and contending?

And more importantly, is there a basis for which you can cultivate awareness and change, or would your energies best be spent elsewhere?

For many of us, our first glimpse of social justice activism was a social media post. Yet so long as we choose to engage at the level of a Twitter argument—which, let’s face it, are rarely productive—we won’t be any closer to creating the better world we dream of.

This is not to say that calling out perceived oppressions in some situations can’t be a valuable practice. But doing so can potentially lead us to categorize and even demonize someone on the basis of some privileged facet of their identity.

Intersectionality teaches us that each individual comprises multiple “potentially conflicting, overlapping identities, loyalties, and allegiances”,17 all of which interact in different ways with power structures and cultural interpretations.18

Given our various identities operate in tandem, it is impossible to focus on one, to the exclusion of all others.19

Judging someone on the basis of a perceived privileged identity thus is reductive and presumptuous, especially when we know often know next to nothing about an online dialogue partner.

Social justice warriors practice self-reflection

Social media platforms, as we all know by now, rely upon algorithms to filter content, biasing what users see in their social media feeds according to what they have previously engaged with.20

This has resulted in an “echo chamber” effect, in which social media users are presented with information that confirms existing biases while ensuring the only contact they have is with others they perceive to be fundamentally similar.

This echo chamber effect has been credited with ushering in an era of post-truth politics, fueling tribalism, fanning the fires of culture wars, and contributing to the extremely polarized state of modern politics in the U.S.

The lack of transparency around how these algorithms operate unfortunately means that our ability to reach many people—especially those of opposing political views—is often limited.

Even more problematic is the fact that these algorithms may lead us into believing our chamber reflects an “essential” conception of reality, rather than one shaped by our values and opinions.

Not being exposed to anything that deviates from this perceived reality can have the effect of reinforcing existing worldviews. We may become less and less aware of our own biases and prejudices and prone to invalidating “the cognitions and realities of those who are different”.21

As aspiring changemakers, we can’t afford to be dogmatic. Rather, we must be willing to step out of our ideological echo chambers, reflect on our own biases, and be open to taking other perspectives.

Only when we do this can we truly “dialogue across difference”22 23 and forge the relationships that are so crucial to change.

In the words of pioneering American social worker Jane Addams: “Social advance depends as much upon the process through which it is secured as upon the result itself”.24

Essy Knopf is a therapist who likes to explore what it means to be neurodivergent and queer. Subscribe to get all new posts sent directly to your inbox.

- Earl, J., & Kimport, K. (2011). Digitally enabled social change: Activism in the internet age. The MIT Press.

- Copeland, P. (2015). Let’s get free: Social work and the movement for Black lives. Journal of Forensic Social Work, 5(1–3), 3–19.

- Miller, J., & Garran, A. M. (2017). Racism in the United States: Implications for the helping professions. Springer Publishing Co.

- Tufekci, Z. (2018). Twitter and tear gas. Yale University Press.

- Phillips, W. (2015). This is why we can’t have nice things: Mapping the relationship between online trolling and mainstream culture (p. 43). MIT Press.

- Freire, P. (1968). Pedagogy of the oppressed, trans. Myra B. Ramos. Seabury Press.

- Harro, B. (2000a). The cycle of liberation. In M. Adams (Ed.), Readings for diversity and social justice, 15–21. Routledge.

- Harro, B. (2000b). The cycle of socialization. In M. Adams (Ed.), Readings for diversity and social justice, 15–21. Routledge.

- Brown, B. (2015). Rising strong. Spiegel & Grau. See also Brown, B. (2012). Daring greatly: How the courage to be vulnerable transforms the way we live, love, parent, and lead. Gotham Books.

- Build, F. (2019, March 31). Pope Francis: ‘Build bridges, not walls.’ America Magazine. https://www.americamagazine.org/faith/2019/03/31/pope-francis-build-bridges-not-walls

- Tutu, D. & Tutu, M. (2014). The book of forgiving: The fourfold path for healing ourselves and our world. Harper Collins.

- Frankl, V. (1984). Man’s search for meaning: An introduction to logotherapy. Simon & Schuster.

- Hepworth, D. H., Rooney, R. H., Dewberry Rooney, G., & Strom-Gottfried, K. (2017). Direct social work practice: Theory and skills (10th ed.). Brooks/Cole.

- Selections from the writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. (2020). Bahá’í Reference Library. https://reference.bahai.org/en/t/ab/SAB/sab-16.html

- Nhat Hahn, T. (2020). The five mindfulness trainings. https://plumvillage.org/mindfulness-practice/the-5-mindfulness-trainings/

- Winfrey, O. (Interviewer) & Hahn, T. N. (Interviewee). (2010). Oprah talks to Thich Nhat Hanh. Retrieved from Oprah.com. http://www.oprah.com/spirit/oprah-talks-to-thich-nhat-hanh/all

- Delgado, R., & Stefancic, J. (2001). Introduction. In R. Delgado & J. Stefancic (Eds.), Critical race theory: An introduction. (2nd ed., p. 9). NYU Press.

- Stevens-Watkins, D., Perry, B., Pullen, E., Jewell, J., & Oser, C. B. (2014). Examining the associations between racism, sexism, and stressful life events on psychological stress among African American women. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 20(4), 561–569.

- Crenshaw, K. W. (1995). The intersection of race and gender. In K. Crenshaw, N. Gotanda, G. Peller, & K. Thomas (Eds.), Critical race theory (pp. 357–383). New Press.

- Tufekci, Z. (2018). Twitter and tear gas. Yale University Press.

- Sue, D. W., Capodilupo, C. M., Torino, G. C., Bucceri, J. M., Holder, A. M. B., Nadal, K. L., & Esquilin, M. (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist, 62(4), 271–286.

- Harro, B. (2000a). The cycle of liberation. In M. Adams (Ed.), Readings for diversity and social justice, 15–21. Routledge.

- Harro, B. (2000b). The cycle of socialization. In M. Adams (Ed.), Readings for diversity and social justice, 15–21. Routledge.

- Addams, Jane. (1922). Peace and bread in the time of war. Macmillan Company.

© 2025 Ehsan "Essy" Knopf. Any views or opinions represented in this blog are personal and belong solely to the blog owner and do not represent those of people, institutions or organizations that the owner may or may not be associated with in professional or personal capacity, unless explicitly stated. All content found on the EssyKnopf.com website and affiliated social media accounts were created for informational purposes only and should not be treated as a substitute for the advice of qualified medical or mental health professionals. Always follow the advice of your designated provider.