How gay dating apps have sparked a vulnerability crisis

My first real contact with the gay community was not through gay dating apps, but one of their predecessors: the website Gaydar.

Aged 17, I had just left the family home and moved to a new city where I knew no one. Being not yet of legal age, I was unable to attend gay nightclubs, so Gaydar swiftly became my exclusive means of contact with other gay men.

Similar to the Scruff of today, Gaydar allowed users to set up a profile along with a private gallery.

Occasionally I’d get a notification that another had unlocked theirs for me. I’d brace myself, dreading what the invitation must inevitably hold.

And sure enough, the moment I clicked through, I’d receive a barrage of “anatomical exam” photos. For many people I’ve talked to, nude photo swaps are more mundane than titillating.

Gay dating apps demand that we market ourselves as a commodity, as an ingredient in a fantasy that can then be mentally reconfigured at will.

When we are presented as just another face or torso in a sea of countless others, we have to take any chance we can to stand out.

If you subscribe to that logic, “showing the goods” is a necessary requirement for a “sale”. I have always questioned however whether this is a tactic that results in face-to-face encounters.

In-person interactions it seems have become an increasingly pallid substitute for the heightened reality of app-based instant gratification.

Exchanging sexual messages and photos with multiple dating app suitors is undeniably fun, especially given it carries none of the effort or consequences of real-life – and double the reward.

These apps by design promote self-objectification and the validation that inevitably follows. They encourage us to respond to others not merely in order to maintain a conversation, but for the inherent reward of receiving a reply.

That reply by implication is an acknowledgment of our romantic or sexual appeal. The positive neural feedback we receive when someone messages or sends us photos reinforces the desire to be objectified, which in turn keeps us coming back for more.

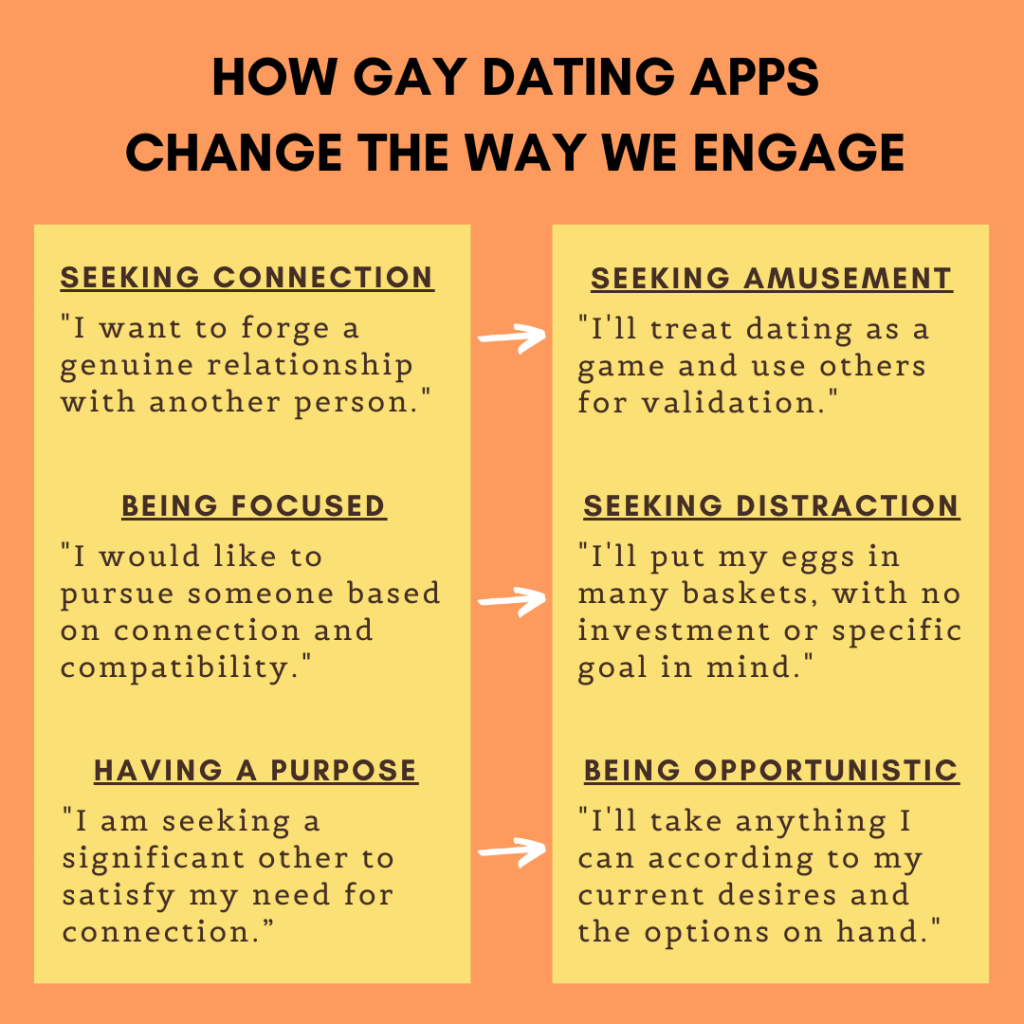

But if we are not mindful, we can develop a single-minded focus on “winning”, leading in some cases to a gay dating app process addiction.

In such cases, the process of dating becomes entirely divorced from its proclaimed purpose: to facilitate real-life relationships.

Table of contents

Gay dating apps demand we sacrifice vulnerability

Gay dating apps discourage exclusivity and encourage the fielding of multiple suitors. It’s a juggling act that necessitates efficiency. With so many options on hand, selecting a romantic or sexual partner must inevitably become a game of elimination.

We screen people, dishing out and receiving rejection over and over again. In order to protect our egos, we give up making genuine approaches.

Instead of being present with the person, we’re speaking with, we slip into safe automaticity: talk round and round in talk circles, replace sentences with monosyllables, prompt people for information we have demanded from countless others before them.

We list requirements and apply filters as if our tastes will maximize our gains and shield us not against failed connection, but an apparently far greater loss: suboptimal pleasure.

In effect, we trade connection for selection, and authenticity for subterfuge. In order to shield our feelings against the possibility of being hurt, we often disengage them entirely.

Why you should say no to nudes

We play it cool, we play it sexy, but we don’t play our complicated, nuanced selves. Why? Because of the inherent limitations of instant messaging, the high levels of scrutiny to which it subjects us, and the wide latitude for misunderstanding.

Our conversations consequently become the rapid informational relay of stockbrokers. Stuck in the emotional deep freeze of gay dating apps, we fall to assessing, objectifying, categorizing and rejecting, arranging and manipulating people as if they were chess pieces, rather than living and breathing beings.

We devalue both our humanness and that of others, and vulnerability dies a quiet death.

The irony is that to be naked is, in a very real, physical sense, to be vulnerable. Exchanging nude photos asks us to put ourselves on display for summary judgment by strangers.

It forces us to be mercenary in our attitudes towards our chat partners, and cavalier about exposing ourselves in a way we normally reserve for intimate occasions.

Arguably one of our primary needs as human beings is to connect with others. To connect, we need to be vulnerable. By sending nude photos, we are denying ourselves that right.

In most cases, my app-based interactions have died in the water the moment I refused to exchange nude photos. To me, others’ demands were reductive and objectifying.

It seemed to be that complying meant becoming yet another item on the app buffet menu. It also rewarded what I saw as unconscious, addictive “lever-pulling” behavior, the kind of thing you would expect of a rat trapped in a Skinner box.

I am sad to report that after such refusals, my chat partners almost always chose not to meet me “sight unseen”. Instead, they continued to linger online, hedging their bets and scoping out all the available options.

Many I suspect never intended to “choose” in the first place, preferring instead to forestall meeting anyone, often for the reasons I’ve already mentioned. Consider the example of the much-maligned “pic collector”, who lurks on the app for the sole gratification of collecting sexual photos.

Be valued – on your terms

Gay dating apps only add to the pressure we face as gay men to conform to a certain ideal image of masculinity, which is often used as the basis for how we are assessed and treated by our romantic or sexual partners.

But this oft-celebrated ideal – perfect cheekbones, chiseled jaws, and an athletic, muscular build – is problematic on several fronts.

First of all, this image is for, at least for a majority of gay men, simply unattainable.

Even those of us blessed with good genes would still be required to invest a significant effort and time into crafting a picture-perfect physique. This is effort and time that most of us are unwilling, or unable, to spare.

Secondly, I believe this image is part and parcel of a toxic cultural perception of masculinity. Namely one in which men are unemotional, self-reliant ubermensch, impervious to any harm.

Beyond popular representations by TV and movie stars, such men do not, and never have, existed.

Thirdly, subscribing to this ideal asks that we divorce ourselves from our inner emotional selves – the same selves for which we crave acceptance.

It follows that the more we try to displace this need in favor of objectifying ourselves on gay dating apps, the more unhappy we are likely to feel.

With such pressures, it’s no surprise that we are living in the midst of a slow-churning mental health epidemic. Gay men are more than twice as likely as their heterosexual counterparts to suffer from a mental health condition. They are also at a higher risk than the general population for suicide.

For this reason, it’s crucial we avoid activities that are likely to put our sense of well-being in harm’s way. Choosing not to expose our naked selves to total strangers before meeting them is not an act of defiance. It’s an act of self-preservation.

Nudity should be an earned privilege that should occur in an atmosphere of mutual respect, not summary judgment.

By refusing to send nude photos, we are reclaiming the right to be valued – on our own terms.

Takeaways

- Gay dating apps keep us trapped in a never-ending cycle of trying to maximize gains.

- The positive reinforcement they offer may lead to a cycle of automatic behavior.

- This cycle may cause us to lose touch with vulnerability and our desire to connect.

- Nude photo exchanges allows strangers to hold our bodies up against some unattainable ideal.

- By not swapping nude photos, we are safeguarding our mental health.

Essy Knopf is a therapist who likes to explore what it means to be neurodivergent and queer. Subscribe to get all new posts sent directly to your inbox.

© 2025 Ehsan "Essy" Knopf. Any views or opinions represented in this blog are personal and belong solely to the blog owner and do not represent those of people, institutions or organizations that the owner may or may not be associated with in professional or personal capacity, unless explicitly stated. All content found on the EssyKnopf.com website and affiliated social media accounts were created for informational purposes only and should not be treated as a substitute for the advice of qualified medical or mental health professionals. Always follow the advice of your designated provider.