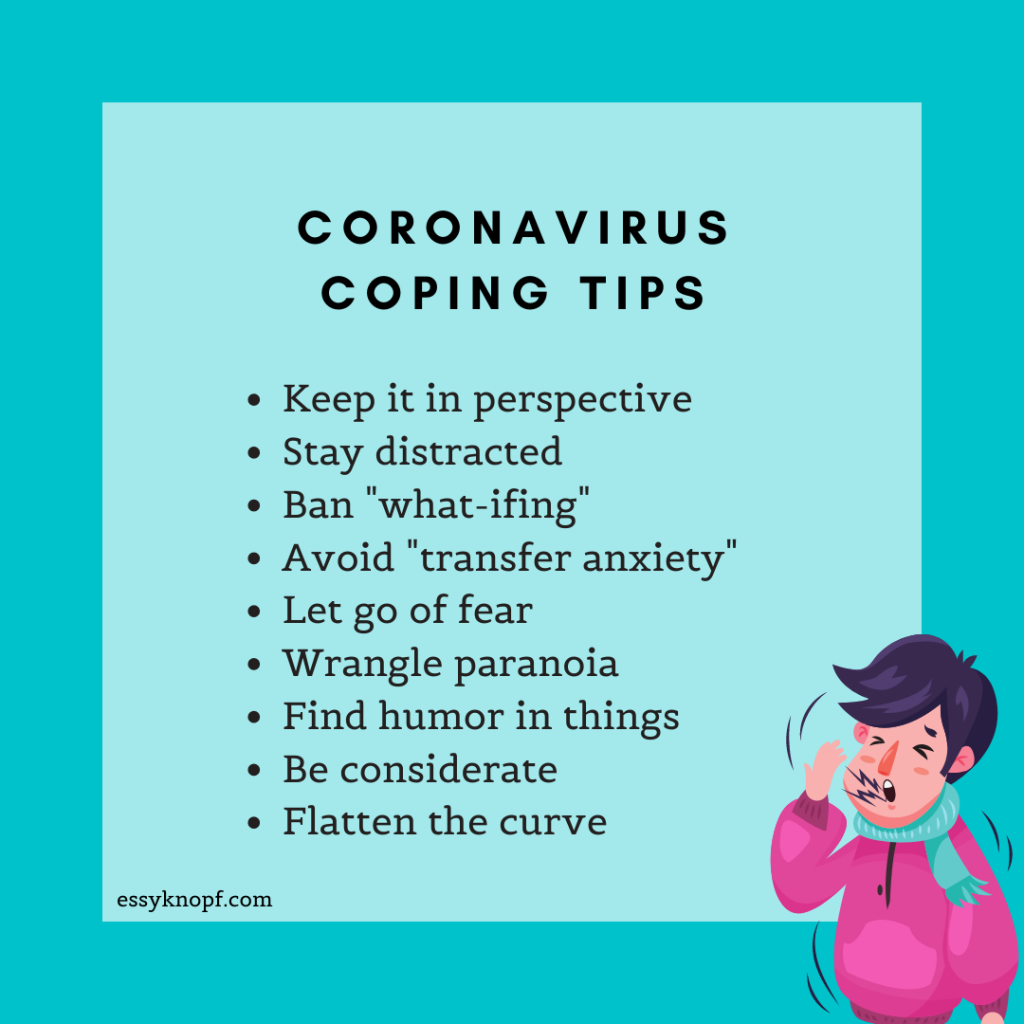

Nine ways to cope with coronavirus crisis insanity

I was in transit from Los Angeles to Australia to visit my parents when the coronavirus crisis well and truly blew up.

As a journalist, I had followed early coverage of the pandemic, then in its infancy. Like most people, I hadn’t expected it to reach the proportions it eventually did.

Having planned this trip five months in advance, I was determined not to let a virus derail my vacation.

A few days later, however, the full gravity of the problem hit home for me – as did my need for some serious coping strategies.

Table of contents

Keep it in perspective

I hadn’t seen my parents in almost two years. I was expecting their undivided attention, but soon after my arrival, they were engulfed by the non-stop coronavirus crisis TV coverage.

Tiring of what I thought to be more of the usual alarmist chatter, I asked them to turn it off.

As all of our conversational topics turned towards coronavirus, I tried steering them towards another topic. I mean, was there any point speculating about something as unprecedented as a global pandemic?

During a trip to the supermarket, I saw many of the shelves had been stripped clean. My only reaction was to roll my eyes.

The checkout operator complained about being unable to buy red meat.

“I told him my boyfriend was going to be getting chicken for dinner and he was NOT happy,” the woman said.

“No red meat?” I wanted to cry. “People are dying and this man is being denied a steak? Of all the injustices…”

Find distraction

As someone who tends towards extreme introversion, I didn’t consider myself a quarantine risk.

Given I spend 95 percent of my time at home in front of a computer, I figured the odds of me getting anything other than an email virus were pretty low.

Besides, I was dealing with crises of far greater personal significance than the coronavirus. Take for example the shaky internet connection at my parent’s home, which dropped out on an almost hourly basis.

Then there was my phone, which refused to take charge and could not be fixed until my return to the US.

Unable to text my friends, I too now faced being swallowed up by the coronavirus news cycle.

The only alternative, as I saw it, was some form of preoccupation.

I dug my Kindle out of my luggage and stared at it. My reading list was waiting. And yet the world as I knew it could be coming to an end.

It was, perhaps in the truest sense, now or never.

Ban ‘what-if-ing’

Only when my airline Virgin Australia announced it was shutting down a week after I was scheduled to leave did I start to fret.

Five minutes after the announcement was made, I tried bumping back my departure online, watching in real-time as flight after flight became full.

Two days prior, a flight change would have come in at $200. By the end of the booking frenzy, ticket changes carried a price tag upwards of $5000.

I was on a shoestring budget, but still, I wondered: should I just bite the bullet and fly out at the soonest opportunity?

I began “what-if-ing”. What if the US or Australia decided to close their borders completely? What if Virgin Australia ended flights even earlier?

Come to think of it, $5000 seemed like a reasonable price for escaping indefinite exile on a mountain with no internet and just my parents for company.

It certainly sounded like a rather bad/good reality TV premise. Throw in a toilet paper shortage and the show would be a hothouse for family drama.

My parents as it turned out had decided to sidestep this issue entirely. Their solution? Purchase bidets for every toilet in the house.

But in the case of my flight, there was no equivalent of a bidet, and thus no point agonizing about worst-case scenarios.

Avoid ‘transfer anxiety’

Over the next few days, I heard reports of grocery shortages in Los Angeles. The next thing I knew, the city had been placed in lockdown.

Friends who share my natural tendency for catastrophizing warned me I might be better off staying in relatively isolated Australia – at least for the immediate future.

Some even insinuated I would, by virtue of boarding an international flight, be a transmission risk to others.

Never mind I had spent the last two weeks in relative isolation from civilization, or that I was sitting at the rear of the plane, away from the potentially contagious horde. And let’s not forget Los Angeles already had multiple cases of coronavirus.

When a relative refused to see me until after a 14-day quarantine period, I was offended.

“What do I look like to you?” I wanted to shout. “Typhoid Mary?!”

Up until this point, my attitude about it all had been rather devil-may-care.

“Bring it on!” I’d say while pummelling my chest. “I’m healthy and in my prime. I’ll beat coronavirus hands down!”

But LA was swiftly becoming a hoarder’s paradise. Looting and martial law seemed like the inevitable next step.

As the hours went by, my anxiety grew. The choice it now seemed was between boarding my flight to a real-life Hunger Games, or canceling my ticket and leaning indefinitely on the hospitality of my folks.

Exhausted by the endless spiral of negative thinking – largely sparked by the worry-mongering of others – I turned off my social media, did my nightly meditation, and went to bed.

Let go of your fear

When I woke up, it was to find I had been endowed with a new spirit of defiance.

While fixing myself a cup of tea, I sneezed. My mother, who had herself sneezed at least a dozen times since I’d arrived from the US, emerged from the bathroom.

“Why are you sneezing, Essy?” she said. I sensed the beginning of an interrogation.

“BECAUSE I HAVE CORONAVIRUS!” I cried. “Here, give me a hug.”

I grabbed for my mother and she pulled away.

Next thing, she was complaining to my father of a sleepless night and being sore. This sent him into a tailspin. “Sore” became “aches and pains”, which became “she has coronavirus”.

My father in his growing terror went racing from the house.

When he returned five minutes later, it was to explain he’d gone to buy face masks for himself and me, only to find that the store was, predictably, out of stock.

“Dad,” I began, “you do realize that mum prepares all of our meals? That she touches the same surfaces as us? The kettle? The fridge? The TV controller?”

“We should still take precautions,” he said.

“DAD,” I replied. “There is no ‘pre’. If mum has it, we already have it.”

I didn’t consider this fatalism, but rather a possibility we would all just have to accept.

Wrangle paranoia

Later, my dad suggested we go for a hike. We arrived to find the narrow trail bustling with tourists.

Despite the difficulty of such an endeavor, my dad insisted on enforcing social distance, which meant we had to stop and start walking constantly to avoid large groups of “potential carriers”.

Each time they passed, my dad would turn his face away from his fellow hikers. He complained they were “breathing all over him”. At one point I even caught him holding his own breath.

When a man ahead of us bellowed, dad seized up, his eyes bulging.

The noise came again, an inarticulate groan. I noticed the man was walking with a cane.

“Come on, Shane,” said a female companion. “It’s alright.”

Still, my father did not move.

“He has a disability, dad,” I told him, “not a contagion.”

At a lookout point, I took to baiting him.

“Don’t put your hand on the railing,” I warned. Dad immediately retracted his hands.

We’d paid a visit to the restaurant where my mother worked. On the car drive back, I cleared my throat.

“You do realize you touched the restaurant door handle twice?”

My dad registered this terrible fact in silence.

When we got home, he insisted I wash my hands and my face. My father proceeded to spray his wallet and every surface he had touched with Lysol, including the car door handles.

“What about the steering wheel?” I said when he came back into the house. “What about your seatbelt? What about the AC controls?”

Tiring of the sassing, my dad raised the Lysol can towards my face.

“What about your mouth?” he growled. Then went back out to the car to complete the job.

Find the humor in things

I intercepted my mother during her morning ritual of filling the bird feeder.

“Are you sure that’s a good idea?” I asked.

“What do you mean?” she asked, pausing.

“With these shortages,” I said, in mock paranoia, “you might need the seeds yourself. You never know.”

My mother only ignored me.

Later that day, at an intersection, we saw a man, his head buried in what looked like a copy of the bible, mumbling verses.

Whatever he was saying was lost to passing motorists. If he’d really wanted to be heard, you’d think he would have tried at least raising his voice.

If I’m going to be honest here, the man was lacking in entrepreneurial initiative. Any end-times preacher worth his salt knows he needs at least a placard and a megaphone.

I mean how are the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse ever going to know their services are needed if their heralds can’t even get their act together?

It was pitiful, really.

Be considerate

My return flight to the US was packed with vacationers and students making an early trip home.

Due to a flight change, the solitary seat I had booked for myself at the rear of the plane now came with a second seat. Worse still, it directly abutted a bathroom.

This basically meant I would be exposed to all foot traffic – namely, potential coronavirus carriers – and worse: the terrible suction noises of the toilet.

As I took my seat, an elderly couple arrived. The woman looked at the seat next to me, her expression rather woeful.

“It looks like they’ve split us up, Rod.”

I stared at her as if to say: “I know what you’re trying here lady, and it’s not going to work”. No way was I giving up my window seat, not even for the coronavirus’ top targets.

“I’m happy to swap seats with you,” chirped a man. He looked like he had just come back from six months of fruit-picking without the benefit of a shaving razor.

Settling into the seat beside me, Fruit-picker produced a bottle of sanitizer and began spraying his hands, the tray table, and the chairback.

It was a ritual he would undertake repeatedly during the trip, spraying and attacking the same surface he had cleaned only an hour before.

“Buddy,” I wanted to say, “we’re sitting next to the toilet. You’re trying to hold back the tide.”

Just before takeoff, I snuck a glance and saw him texting someone.

“Almost lost it at some kid behind me in the queue,” Fruit-picker typed.

“He kept hitting my backpack. No idea of personal space.”

Then for the remainder of the flight, he proceeded to invade mine.

Most people would consider the armrest the demarcation line between seats. Not my fellow traveler. Not only did he claim the rest for himself, but also part of my seat too.

Every time he rearranged his blanket or the contents of his tray table, I copped an elbow. Over and over, he would nudge me, without a whisper of apology.

When I attempted to fall asleep, I was awoken by yet another elbow graze and the astringent odor of the sanitizer.

By the time we touched down in Los Angeles, part of me was deeply regretting having not just taken my chances on the mountain.

Neither of us had wanted to board that crowded flight and brave the risk of contamination. But I’m equally confident a little more social distancing on Fruit-picker’s behalf might’ve made all the difference.

Flatten the curve

Look, only a pundit aching for a faceplant or someone with a very accurate crystal ball would try to predict how serious the coronavirus crisis will get.

Whatever the outcome, we all as individuals have limited agency. We do however have a responsibility to help flatten the curve.

A simple way to do this is by respecting national health department recommendations for maintaining social distance and personal hygiene practices.

We have as much influence over our behaviors as we do over our mindsets. Though given the uncertainty surrounding the current global situation, none of us could be blamed for worrying.

If you catch yourself becoming overwhelmed with stress and anxiety, ask yourself: are you taking the steps you need in order to feel better?

More information about the coronavirus/COVID-19 epidemic here.

Takeaways

- The world is not ending. Keep things in perspective.

- Stay occupied and suspend endless worrying.

- “Quarantine” yourself from situations likely to result in transfer anxiety.

- Put on your “humor” spectacles and look for a new reason to laugh.

Essy Knopf is a therapist who likes to explore what it means to be neurodivergent and queer. Subscribe to get all new posts sent directly to your inbox.

© 2025 Ehsan "Essy" Knopf. Any views or opinions represented in this blog are personal and belong solely to the blog owner and do not represent those of people, institutions or organizations that the owner may or may not be associated with in professional or personal capacity, unless explicitly stated. All content found on the EssyKnopf.com website and affiliated social media accounts were created for informational purposes only and should not be treated as a substitute for the advice of qualified medical or mental health professionals. Always follow the advice of your designated provider.