Anxious Seeks Canine – Part 10: ‘Annul anarchy’

Anxious Seeks Canine is a memoir blog series about a gay man living with Asperger’s, mental illness, and the relationships that may very well be fueling it. Names and identifying details have been changed to protect the privacy of all featured individuals. Except for the dog. Here’s part 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, and 18. Subscribe for more posts.

I

“Um, excuse me…” I looked up from my book. A woman I didn’t recognize was standing over me. “Your dog…”

Somewhere behind her, an overly ambitious Cash was trying to mount a rather large Airedale Terrier.

“Oh God, I’m so sorry,” I said, clapping to get his attention. “Cash!”

Cash continued thrusting away at the Terrier’s hindquarters. Only when I rushed towards the scene of the unfolding crime did he stand down.

It didn’t take long however before Cash was circling the Airedale Terrier, in readiness for yet another attempt.

“That’s it!” I snapped. Plucking up Cash, I hauled him over to the enclosure fence – my version of corner time.

Cash’s collar gripped tight in one fist, I muttered in his ear.

“If you keep this up, I’m not going to bring you here anymore. Do you understand?”

By Cash’s wriggling, it was clear that he did not. My dog was as restless and unrepentant as ever.

Knowing what I did about his antisocial tendencies, bringing him back to the park had been the real mistake.

But what kind of owner would I have been if I had left Cash stuck indoors for hours, while I lounged outside in the sunshine?

Cash wasn’t the kind of dog who would sit contentedly with you on the picnic mat. The few times we had tried, he had whined and tried wriggling away from me.

Dog parks were the only off-lead enclosures that I knew of in central Los Angeles. And given Cash’s tendency to battle-charge each and every dog he saw, letting him roam free anywhere else would be to provoke misfortune.

Here at least, the worst thing I would have to face was the hostility of other owners. The judgment seemed to come off them like heat shimmering above boiling asphalt.

Rather than crumple before the steely stares of my peers, however, I rebounded with defiance. This wasn’t a playgroup for toddlers, and no amount of browbeating was going to make me exclude my dog from the rough-and-tumble to which he was entitled.

Okay, yes – Cash’s behavior was, to put it mildly, annoying. But so far as I could see, his offenses paled in comparison to those of some peers.

The types who, for example, jumped up onto tables and stepped all over my laptop while I was smashing out important emails.

“No,” I’d say, pushing them away. “Tables are not for dogs. Tables are for humans.”

It was a declaration almost always punctuated with a glare, directed at their phone-preoccupied owners. Never mind I spent most of my own visit staring at a screen – couldn’t these people see I was trying to work here?!

If the dog park was the stage upon which the dramas of human existence played out in a miniature, abbreviated form, then the sheltered tables where owners sat was an arena for the psyche.

Here, anxiety brewed and fears emerged; shame was inflicted and justifications employed; neuroses fledged and inferiority complexes given vent.

We troubled owners were bound by a code of mutual policing, a code led by volunteer welfare warriors, a character which the park never seemed short of.

On one occasion, I saw a grizzled man in grease-smeared mechanics’ overalls wandering the park, approaching people to ask if they were the owner of an emaciated greyhound.

“He looks borderline starved,” the Welfare Warrior complained. I watched the greyhound lope excitedly after another dog.

“He seems pretty happy to me,” went my response.

Of course, the man only went on with his moral census-taking, determined to hold someone to account.

II

He was, of course, in good company. Whenever I wasn’t doing work, you could almost certainly catch me scrutinizing other owners.

There was the young Korean couple who pent two hours doting on and documenting their crucifix-wearing Golden Retriever with their camera phones.

Grimacing, I watched as the wife cupped her hands while her husband filled the improvised dog bowl with bottle spring water, in an apparent snub of the communal water bowl just a few feet away.

Watching them, I was struck by an impression of adoring parents, following their toddler’s first steps.

The impression was completed when the dog squatted to do her business, and the owners produced a toilet roll and wiped their pet’s underparts.

There was also the woman in activewear who glided over to the table where I was working, plopping a bag full of dog waste beside me.

At first, I didn’t notice. It was not until I caught a whiff of the bag’s contents and looked up that I realized what had happened.

A casual scan of the park revealed Activewear Lady standing on the far side, in the shade, chatting obliviously with another owner.

It took a full forty-five minutes – yes, I counted – before the woman returned to retrieve her bag.

“Sorry about that!” she said.

“No problem,” I lied. The belated acknowledgment wasn’t enough. What I wanted was an explanation. “I just assumed you were keeping it for a stool test.”

“Oh, no,” Activewear Lady rushed to say. “Every time we come to the park, my dog poops twice, three times. So I try to conserve plastic, you know?”

She hefted her doggy bag holder demonstratively.

I raised an eyebrow. How had this woman managed to monitor her dog’s bowel movements and yet fail to notice the numerous bins and pooper scoopers strewn about the park?

Cataloging my fellow owners, I would be remiss in not mentioning the parent of a perpetually happy Labrador who spent her entire visit to the park mesmerized by shadows.

It was not until the third occasion of our meeting that I worked up the courage to approach the man with tattooed sleeves and ask him about his dog’s fixation.

“Oh that,” Tattooed Sleeves said, laughing in what sounded like dry amusement. “She’s a shelter dog. Her last owner left her on her own for long periods.”

“Poor thing,” I tutted.

“So now she thinks shadows are people,” Tattooed Sleeves concluded.

My gaze returned to the Labrador, who had not only failed to register the other dogs frolicking around her, but had spent the past 20 minutes watching shadows, tail wagging a merry greeting.

“And that doesn’t worry you.” It was both a statement and a question.

“The vet says it’s just her way of coping,” Tattooed Sleeves said. He shrugged. “She seems to enjoy it.”

With all this dysfunction around us, I certainly felt Cash and I were among equals. Yet visiting the dog park was about as socially trying for my pet as it was for me.

Most visits, I shied from talking to other owners, handicapped as I was by my sense of being an imposter. While I might have had a pet, I was by no means a good owner.

A good owner, after all, was a person of certain insight, skill, and wherewithal – qualities I certainly admired, but did not have.

And then there was the fact that while I might love Cash…I didn’t quite like him.

These facts I feared were an open secret. To everyone who saw me, I was that guy: the neglectful novice who didn’t care to train his rowdy dog.

The sense of deficiency extended as much to me, as to Cash. I might tell him he was a “good dog”, and yet part of me wondered, “But is he? Really?”

But Cash was, in this sense, an heir to a legacy of my own self-doubt.

III

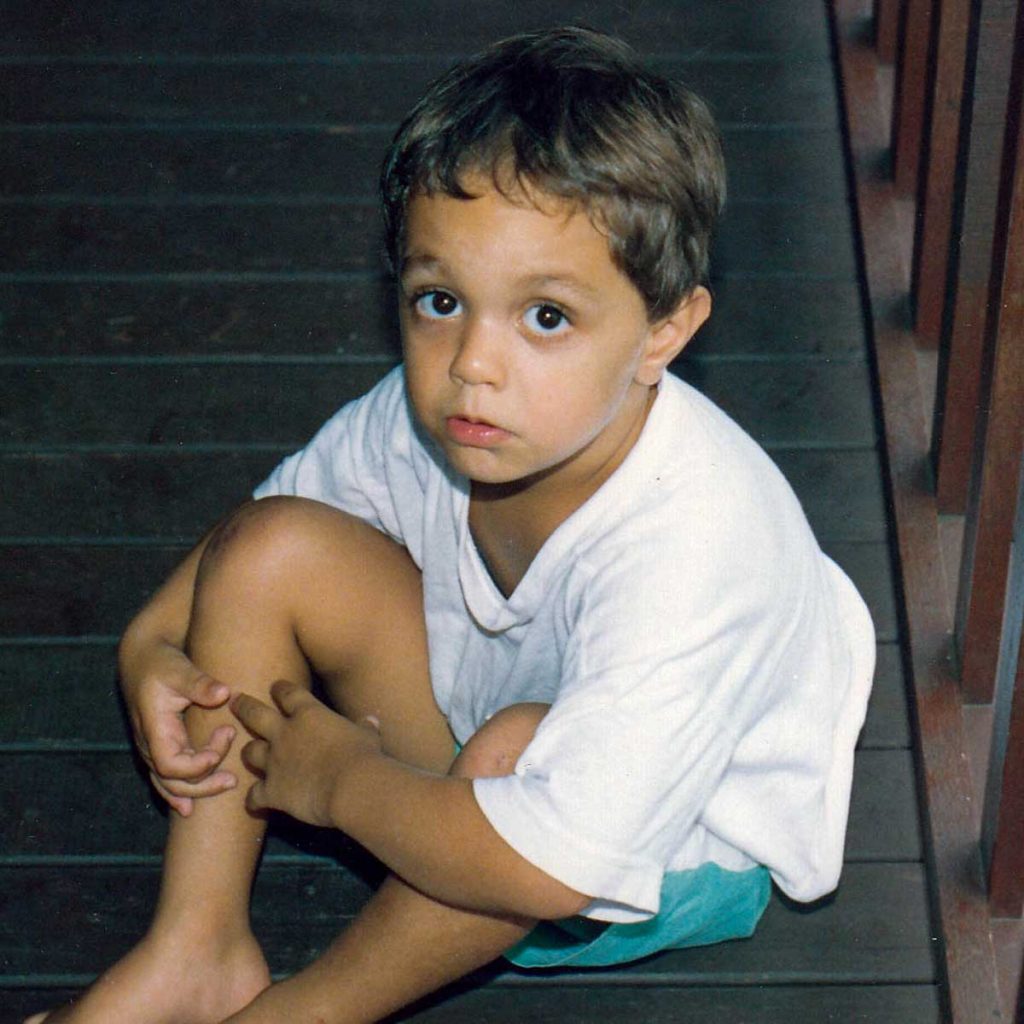

From pre-K on, I’d known with painful certainty that I wasn’t like the other kids.

At six, I began memorizing the Latin names of dinosaurs. My interest progressed to Lego, then insects, gemstones, coins, stamps, Pokémon cards, and words.

Yes, words. As a grown adult, I’d open my childhood keepsake box to find ratty little lists of them.

There were other things, such as sensory sensitivities. Underwear that seemed to intentionally – no, sadistically – rub my privates. My family, loudly chewing their dinner.

The intense discomfort of being tickled, so intense I’d once felt compelled to scream “Rape!” in order to fully convey my sense of violation.

In some areas of academia, like reading, I’d excel, while in others, I’d struggle, nearly flunking basic arithmetic in my second year.

Writing with a pencil felt like doing needlepoint with a mop. My distinctions didn’t end there. There was also the fact I had to ask the teacher’s help tying my shoelaces a full year after everyone else had stopped.

My tendency to take everything literally made idiomatic language a nightmare. The first time I heard Britney Spears’ “Hit Me Baby One More Time”, I thought it was an invitation to spousal abuse.

Words were often mispronounced. Hyperbole became hyper-bole; mortgage, mort-gage; crocheting, crotch-eting.

At 11, I’d passed the porno section of our local video store and caught myself reading the confusing titles aloud. One featured a woman exposing her backside, and carried the title “A-nnul Anarchy”.

Annul anarchy. To banish chaos. It was a concept my inner control freak immediately warmed to.

Despite all my best intentions, I’d stumble into socially inappropriate behavior. On one occasion, while obsessively collecting phone numbers, I asked a high school teacher if I could add hers to my new electronic organizer. That went down about as well as you can imagine.

The act of collecting in and of itself both thrilled, and calmed; conveyed a sense of living in a safe, ordered universe.

Requests like these ran in tandem with disastrous, often ill-timed comments. Once, thinking I was being funny, I complimented a stranger on his nice, strong stream – while he was standing at the urinal.

Raised eyebrows, polite smiles, and dismissals quickly taught me to reign it in. Those times I couldn’t compensate for my shortcomings, I simply withdrew.

But my desire to blurt, to offer unsolicited opinions and stream-of-consciousness admissions was irresistible. Inevitably I’d catch myself flinging matches at wooden bridges – or gaping at the resulting inferno.

One time, I questioned a work colleague’s decision to sell milk chocolate – of all unhealthy foods! – to fund her friend’s bowel cancer treatment. It was, as I insinuated, “completely illogical”.

Like the classic Star Trek character, Spock, or his spiritual successor the android Data, I just didn’t get human beings – and they didn’t get me.

In the face of constant misunderstandings, my pride rebelled. The problem wasn’t me, but these ignoramuses.

How was it that I was always cast as the villain, when I was only being my authentic, good-intentioned self?

For all I might have tried to defy the accusations, I still shouldered a vague sense of guilt. Guilt in turn fuelled questions.

Was I indeed somehow inferior; inherently unlikeable? Did my difference leave me destined for solitude?

It wasn’t until the age of 25 that I received a diagnosis of Asperger’s syndrome, a so-called “high-functioning” form of autism.

The diagnosis drew back the curtains of confusion; let me at last bathe in the light of clarity. Here, at last, was the source of all my challenges – and an explanation for how I could finally overcome them.

Yet, years later, some of the darkness remained. It loomed beneath me, an acid bath of shame as I walked a careful tightrope of dog parenthood.

Anxious Seeks Canine continues with Part 11: ‘This again?’.

Essy Knopf is a therapist who likes to explore what it means to be neurodivergent and queer. Subscribe to get all new posts sent directly to your inbox.

© 2025 Ehsan "Essy" Knopf. Any views or opinions represented in this blog are personal and belong solely to the blog owner and do not represent those of people, institutions or organizations that the owner may or may not be associated with in professional or personal capacity, unless explicitly stated. All content found on the EssyKnopf.com website and affiliated social media accounts were created for informational purposes only and should not be treated as a substitute for the advice of qualified medical or mental health professionals. Always follow the advice of your designated provider.